Forums

- Forums

- Duggy's Reference Hangar

- IJAAF Library

- The Akutan Zero

The Akutan Zero

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

12 years agoWed Dec 21 2022, 10:27pmDuggy

Main AdminOver the last few weeks some interesting shots became available

Main AdminOver the last few weeks some interesting shots became available

So the story.

On June 4, 1942, Japanese air forces raided Allied positions in the Aleutian Islands in an attempt to lure U.S. naval power away from the impending Battle of Midway. When Japanese pilot Tadayoshi Koga took a crippling hit from ground fire and crashed on Akutan Island, the U.S. Navy captured his plane?the coveted Japanese ?Zero.? Koga literally handed the Allies the keys to defeating Japan in the air, helping bring an end to World War II, in the Pacific.

When Koga took off for Dutch Harbor that June morning, he probably expected to complete his mission and return to base as usual. Things didn?t work out that way. Emerging from the ubiquitous fog that envelopes the entire Aleutian Islands chain five or six days a week, Koga acquired his target and strafed the enemy base. During the engagement, his plane took ground fire that severed its main oil line. Now, piloting a fighter trailing a stream of oil, Koga realized that the moment the last drop of lubricant spilled out, his plane?s engine would seize and his Zero would plummet to earth.

With mere minutes to get the plane down safely, Koga headed west for Akutan Island. Designated by the Japanese army as an emergency landing field, Akutan boasted a long, grassy strip that must have looked to Koga like a sure bet for a smooth landing. That turf concealed a trap, though: Boggy soil lurked just below what appeared to be a solid landing strip. The bog snared Koga?s landing wheels and flipped the Zero end over end. It came to rest upside-down.

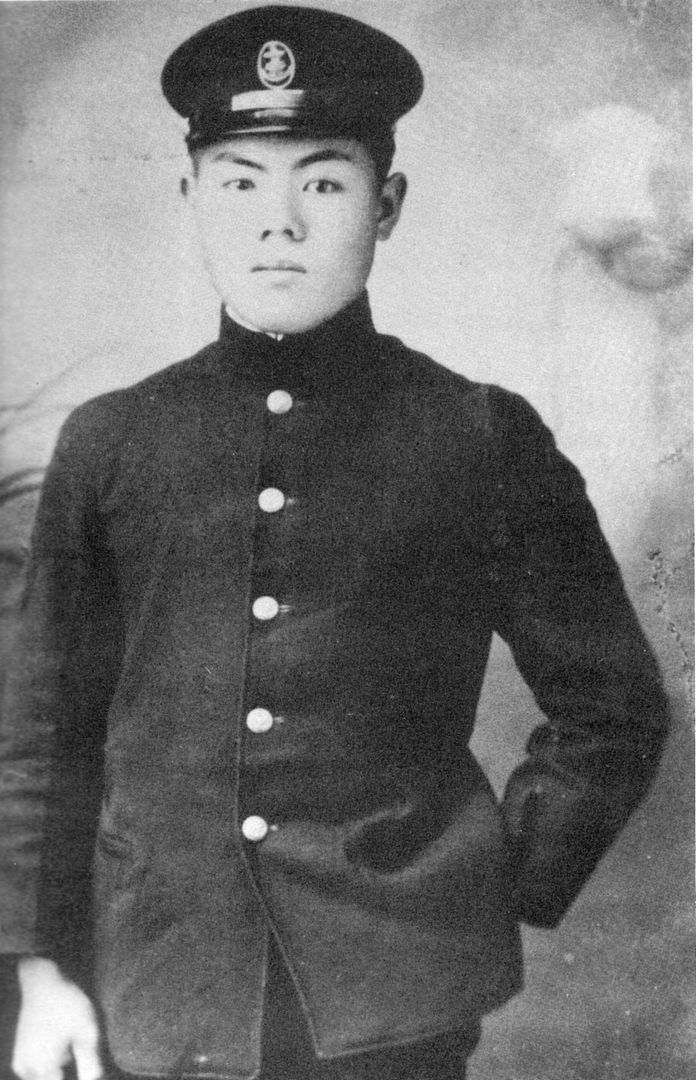

Tadayoshi Koga just after being hit by AA

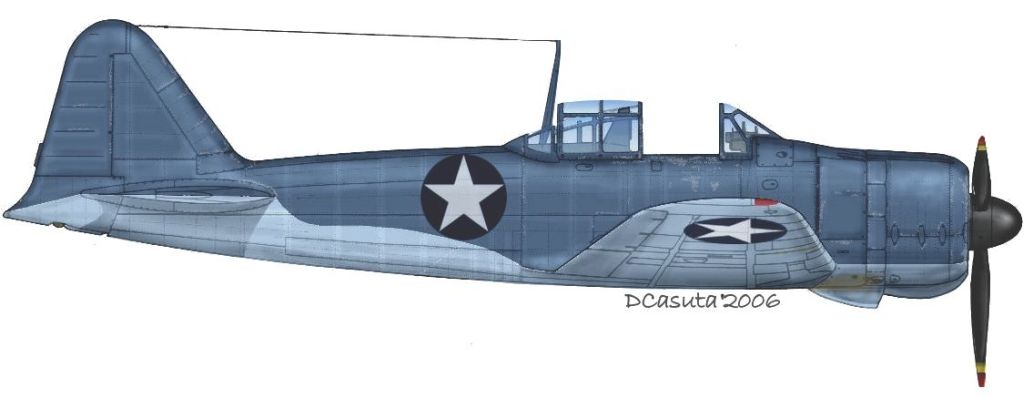

Until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, most American servicemen had never seen a plane like the ?Zero,? so named not because of the prominent Rising Sun emblem painted on the side but for the manufacturer?s type designation: Mitsubishi 6M2 Type 0 Model 21. Those servicemen had heard of the Zero?s reputation, though. Fast and powerful, it was known as a nearly invincible fighter plane with a 12:1 kill ratio in dogfights with the Chinese as early as 1940. The Zero cemented its reputation in an April 1942 battle with well-trained English pilots over Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). In that sortie, 36 Zeroes took on 60 British aircraft?and shot down 27 of them, with the loss of just a single Zero. So formidable was the Zero that the official American strategy for pilots attacked by the Japanese fighter boiled down to this: run away.

It?s curious, then, that Japan allocated any of its mighty fighter planes to an attack on the Aleutian Islands in June 1942 instead of saving them all for the massive campaign it was poised to mount at Midway Island. In fact, no one knows exactly why Japan invaded the Aleutians. The inhospitable chain of 120 small islands sweeps westward some 1,000 miles from mainland Alaska into the Pacific Ocean. Uniformly barren and rocky, the islands offer no support for human settlement. Some historians believe the Aleutian attack was an attempt by Japan to lure American naval power away from Midway Island, which would make an Imperial victory there easier. Others think Japanese troops planned to island-hop through the Aleutians to Alaska Territory, and then invade the mainland United States through Canada.

All Japanese pilots had standing orders to destroy any disabled Zeroes lest they fall into enemy hands. Koga?s plane appeared so undamaged, however, that his wingmen couldn?t bring themselves to shoot it up, fearing they might kill their friend. They circled once or twice before returning to their aircraft carrier at the western end of the island chain. Koga hadn?t survived, however: His neck had broken when the plane flipped over. And he and his Zero lay in the mist on Akutan, just waiting to be discovered by the Allies.

On July 10, as the world?s attention focused on the pivotal Battle of Midway, a U.S. Navy pilot on routine patrol over the Aleutians spotted Koga?s wreckage through a break in the clouds. But Akutan Island would not give up its prize easily. After three recovery attempts, the Navy finally managed to capture the plane and send it to a base in San Diego, California, for restoration. At last, the Zero?s secrets would be revealed.

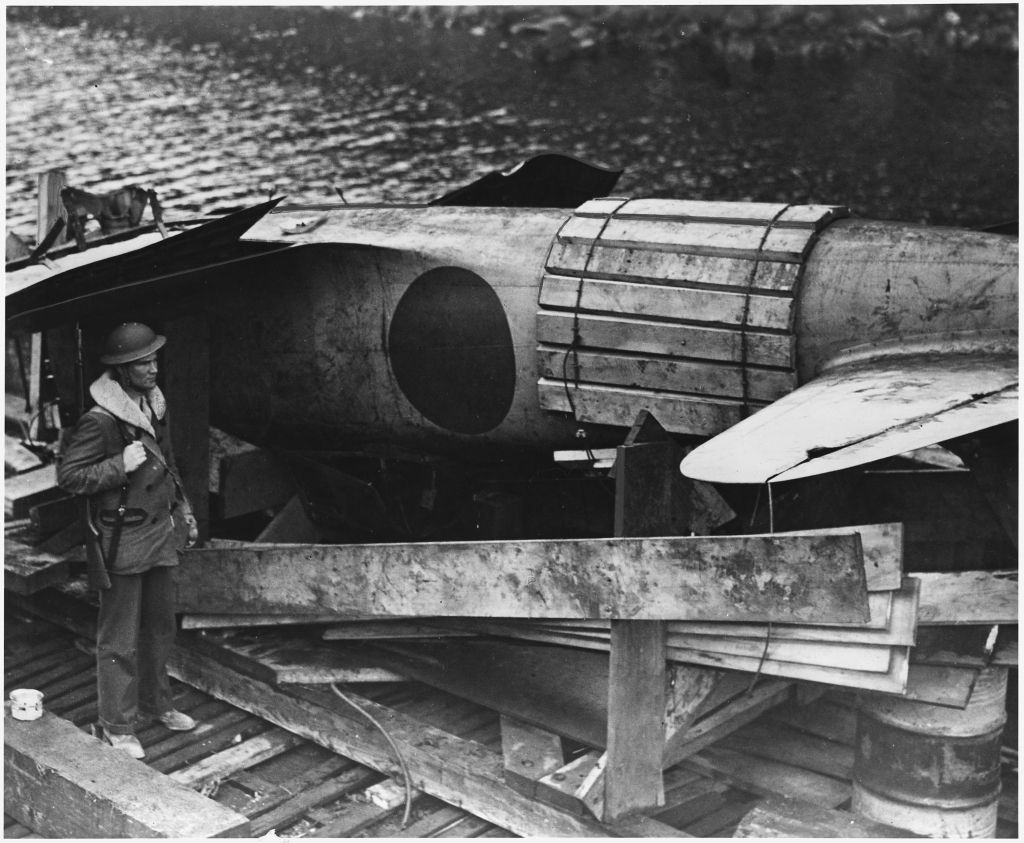

Below Tadayoshi Koga on landing on the "BOG" the aircraft flipped, breaking his neck.

The crashed aircraft was located by piloted US Navy Lieutenant William Thies (left), pilot of a Consolidated PBY-5A Catalina of patrol squadron VP-41, Fleet Air Wing 4.

BELOW RECOVERY

TAKEN ON THE DOCK

PART 2 to follow

-

Level 7Wow! What a reading with photographic documentation.

Level 7Wow! What a reading with photographic documentation.

-

12 years agoFri Jan 10 2014, 08:06pm

Main AdminPart 2

Main AdminPart 2

Thanks to Elizabeth Hanes, for parts of the text.

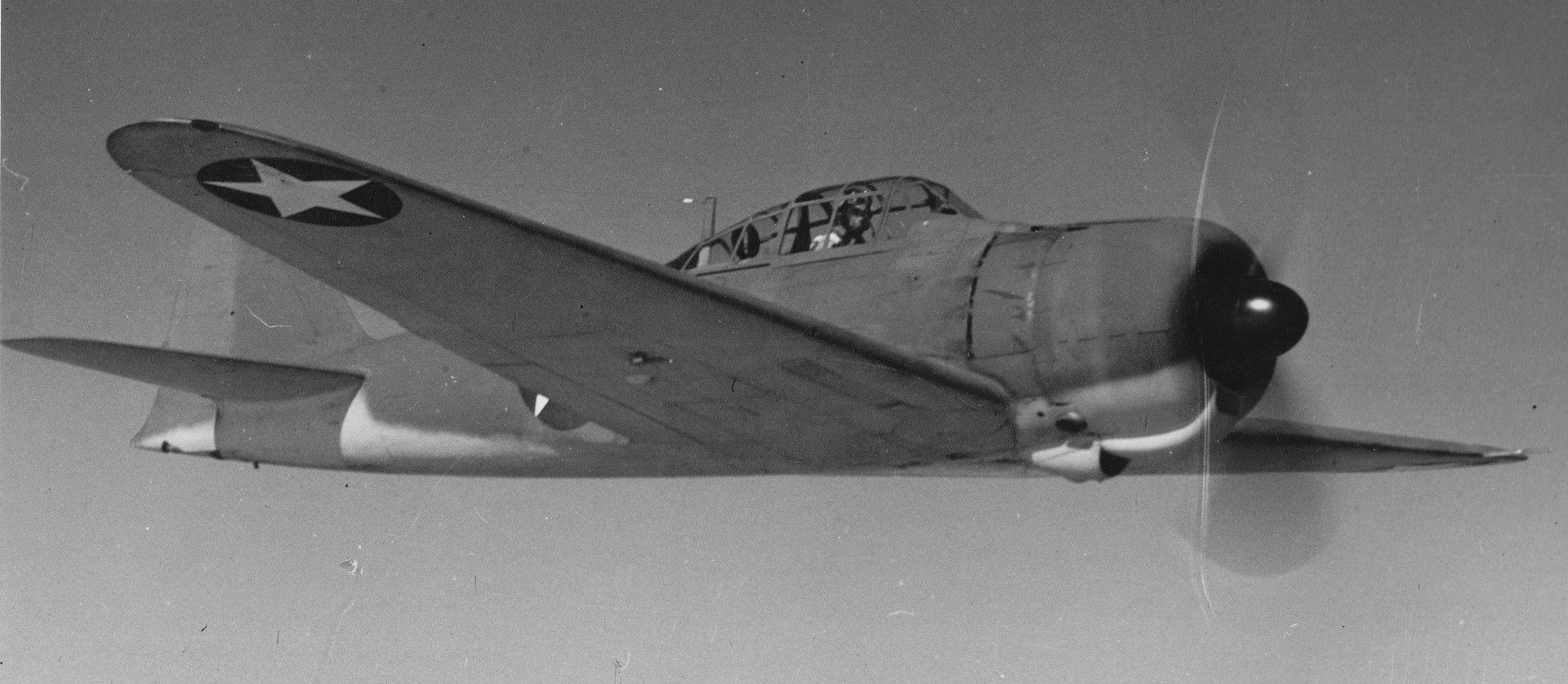

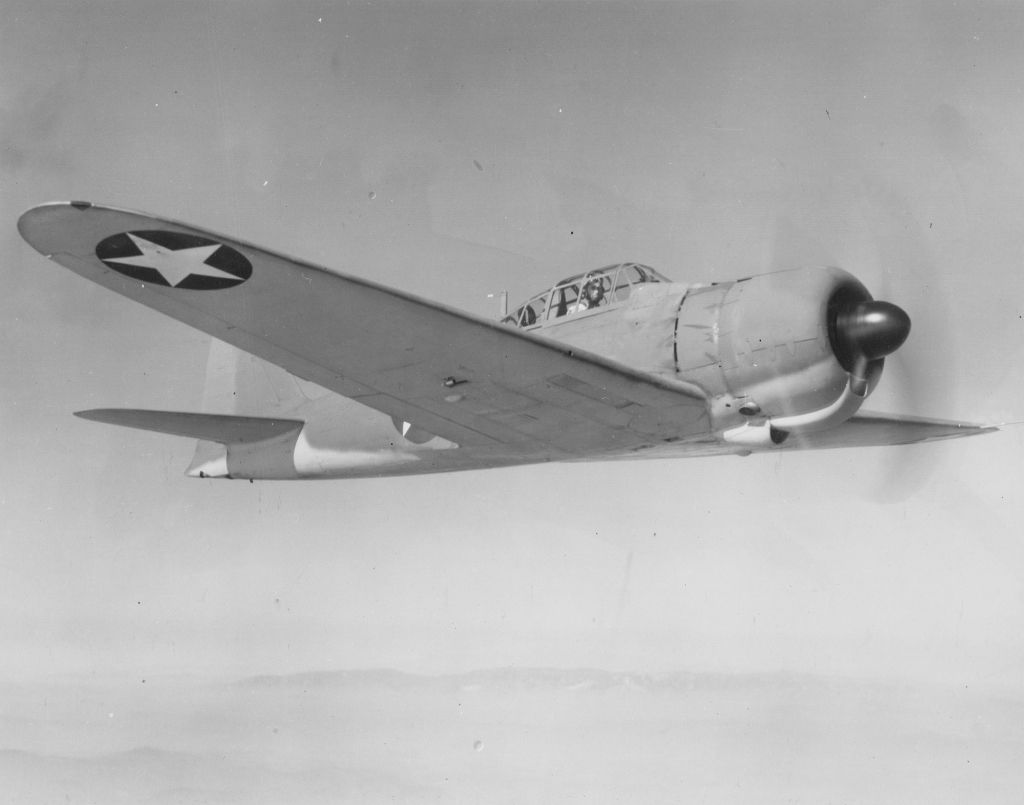

Salvaging what they could and fabricating the few new parts needed, Navy mechanics brought the plane back up to flying condition. On September 20, Lieutenant Commander Eddie Sanders became the first pilot to fly a Zero in American colors. The plane performed beautifully, and Sanders went on to fly 24 test flights in 25 days. In the process, he discovered the Zero possessed not one but two Achilles? heels. First, it was nearly impossible to perform rolls at moderately high speeds. This meant that forcing the enemy into such a maneuver would confer a tactical advantage to Allied pilots. Second, a poorly designed carburetor caused the engine to sputter badly when the plane was placed into a dive at a high rate of speed. Thus, forcing the Zeroes to dive during a dogfight might make them easy targets for Allied gunners.

Now armed with the knowledge needed to best the Zero in combat, the Allies quickly formulated strategies to defeat the Japanese in the air and, just as importantly, demystified the plane?s aura of invincibility. As quoted in Jim Rearden?s book ?Cracking the Zero Mystery,? Marine Captain Kenneth Walsh described how he used information from the Zero test flights to finish the war with 17 aerial victories over Zeroes: ?With [a] Zero on my tail I did a split S, and with its nose down and full throttle my Corsair picked up speed fast. I wanted at least 240 knots, preferably 260. Then, as prescribed, I rolled hard right. As I did this and continued my dive, tracers from the Zero zinged past my plane?s belly. From information that came from Koga?s Zero, I knew the Zero rolled more slowly to the right than to the left. If I hadn?t known which way to turn or roll, I?d have probably rolled to my left. If I had done that, the Zero would likely have turned with me, locked on, and had me. I used that maneuver a number of times to get away from Zeros.?

Using these new air tactics over the ensuing months, the Allies won battle after battle in the Pacific, and the Zero?once the pride of the Japanese air force?was reduced to a kamikaze vehicle. Masatake Okumiya, a Japanese officer who led many Zero squadrons and authored the book ?Zero,? described the significance of the Allies? capture of Koga?s plane as ?no less serious than the Japanese defeat at Midway? and said it ?did much to hasten our final defeat.?

As for Koga?s Zero, the plane met its end in anticlimactic fashion. The craft that handed the Allies the key to winning the Pacific air war was hit by a Curtis SB2C Helldiver plane while taxiing out for a training run; it was reportedly demolished, with only a few small instruments left intact. It was an inglorious finale for an important piece of U.S. war history.

ANOTHER SIDE

Data from the captured aircraft was submitted to BuAer and Grumman Aircraft for study in 1942. The U.S. carrier-borne fighter plane that succeeded the F4F Wildcat, the F6F, would be tested in its first experimental mode as the XF6F-1 prototype with an under-powered Wright R-2600 Twin Cyclone 14-cylinder, two-row radial engine on 26 June 1942. The first production F6F-3 had been designed with specific "Wildcat vs Zero" input from Battle of the Coral Sea and Battle of Midway veteran F4F pilots such as Jim Flatley and Jimmy Thach, respectively, among several others, obtained during a meeting with Grumman Vice President Jake Swirbul at Pearl Harbor on 23 June 1942. It led to the creation of the F6F Hellcat that took off in October 1942. While the captured Zero's tests did not drastically influence the Hellcat's design, they did give knowledge of the Zero's handling characteristics, including its limitations in rolling right and diving. That information, together with the improved capabilities of the Hellcat, were credited with helping American pilots "tip the balance in the Pacific". American aces Kenneth A. Walsh and R. Robert Porter, among others, credited tactics derived from this knowledge with saving their lives. James Sargent Russell, who commanded the PBY Catalina squadron that discovered the Zero and later rose to the rank of admiral, noted that Koga's Zero was "of tremendous historical significance." William N. Leonard concurred, describing it thus: "The captured Zero was a treasure. To my knowledge, no other captured machine has ever unlocked so many secrets at a time when the need was so great."

Some historians dispute the degree to which the Akutan Zero influenced the outcome of the air war in the Pacific. For example, the Thach Weave, a tactic created by John Thach and used with great success by American airmen against the Zero, was devised by Thach prior to the attack on Pearl Harbor, based on intelligence reports on the Zero's performance in China.

The capture and flight tests of Koga's Zero is usually described as a tremendous coup for the Allies as it revealed the secrets of that mysterious aircraft and led directly to its downfall. According to this viewpoint, only then did Allied pilots learn how to deal with their nimble opponents. The Japanese could not agree more ... Yet those naval pilots who fought the Zero at Coral Sea, Midway, and Guadalcanal without the benefit of test reports would beg to differ with the contention that it took dissection of Koga's Zero to create tactics that beat the fabled airplane. To them the Zero did not long remain a mystery plane. Word quickly circulated among the combat pilots as to its particular attributes. Indeed on 6 October while testing the Zero, [Akutan Zero test pilot Frederick M.] Trapnell made a highly revealing statement: 'The general impression of the airplane is exactly as originally created by intelligence?including the performance'.

However, 9 wrecked Mitsubishi A6M Zeros were recovered from Pearl Harbor shortly after the attack in December 1941, and United States Naval Intelligence, along with the Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics had them studied, and then shipped to the Experimental Engineering Department at Dayton, Ohio in 1942. It was noted that the experimental Grumman XF6F-1s then under-going testing in June 1942 and the Zero had "wings integrated with the fuselage," a design feature not normally practiced in American aircraft production at that time.

The Akutan Zero was destroyed during a training accident in February 1945. While the Zero was taxiing for a take-off, a SB2C Helldiver lost control and rammed into it. The Helldiver's propeller sliced the Zero into pieces. From the wreckage, William N. Leonard salvaged several gauges, which he donated to the National Museum of the United States Navy. The Alaska Heritage Museum and the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum also have small pieces of the Zero.

In an attempt to repatriate Koga's body, American author Jim Rearden led a search on Akutan in 1988. He located Koga's grave, but found it empty. Rearden and Japanese businessman Minoru Kawamoto conducted a records search. They found that in 1947 Koga's body was exhumed by an American Graves Registration Service team and re-buried on Adak Island, further down the Aleutian chain. The team, unaware of Koga's identity, marked his body as unidentified. The Adak cemetery was excavated in 1953, and 236 bodies were returned to Japan. The body buried next to Koga (Shigeyoshi Shindo) was one of 13 identified; the remaining 223 unidentified remains were re-interred in Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery in Japan. It is probable that Koga was one of them. Rearden later wrote the definitive account of the Akutan Zero.

Whatever the rationale, sending Zeroes to the Aleutians would prove to be a critical intelligence error for Japan. On June 4, with orders to bomb the Allied base Dutch Harbor on Unalaska Island, young pilot Tadayoshi Koga, thought to have been 19 years old, strapped himself into his plane and prepared to carry out the mission of the Imperial Army. Little is known about Koga. In an undated service photo, he looks directly into the camera, almost smiling, his left hand tucked into the pocket of his uniform. Confident? Definitely. Perhaps even showing a bit of swagger. But then, what Japanese pilot wouldn?t swagger with the indomitable Zero at his command?

-

Level 1Excellent stuff, Duggy. Thanks for posting.

Level 1Excellent stuff, Duggy. Thanks for posting.

Derek -

Level 1I agree with mudpuppy. Great job (again)! Thanks.

Level 1I agree with mudpuppy. Great job (again)! Thanks.

Robert -

Level 1This was a great war story. I knew some of it up to Koga's crash and his broken neck. The rest of the story is amazing history.

Level 1This was a great war story. I knew some of it up to Koga's crash and his broken neck. The rest of the story is amazing history.

Thanks

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources