Forums

- Forums

- Duggy's Reference Hangar

- USAAF / USN Library

- Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk

Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources

-

Main AdminPart 1,The Airships

Main AdminPart 1,The Airships

USS Los Angeles (ZR-3)

USS Los Angeles was a rigid airship, designated ZR-3, which was built in 1923–1924 by the Zeppelin company in Friedrichshafen, Germany, as war reparation. It was delivered to the United States Navy in October 1924 and after being used mainly for experimental work, particularly in the development of the American parasite fighter program, was decommissioned in 1932.

Design

The second of four vessels to carry the name USS Los Angeles, the airship was built for the United States Navy as a replacement for the Zeppelins that had been assigned to the United States as war reparations following World War I, and had been sabotaged by their crews in 1919. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles Luftschiffbau Zeppelin were not permitted to build military airships. In consequence Los Angeles, which had the Zeppelin works number LZ 126, was built as a passenger airship, although the treaty limitation on the permissible volume was waived, it being agreed that a craft of a size equal to the largest Zeppelin constructed during World War I was permissible.

The airship's hull had 24-sided transverse ring frames for most of its length, changing to an octagonal section at the tail surfaces, and the hull had an internal keel which provided an internal walkway and also contained the accommodation for the crew when off duty. For most of the ship's length the main frames were 32 feet 10 inches (10.01 m) apart, with two secondary frames in each bay. Following the precedent set by LZ 120 Bodensee, crew and passenger accommodation was in a compartment near the front of the airship that was integrated into the hull structure. Each of the five Maybach VL I V12 engines occupied a separate engine car, arranged as four wing cars with the fifth aft on the centerline of the ship. All drove two-bladed pusher propellers and were capable of running in reverse. Auxiliary power was provided by wind-driven dynamos.

Operational history

Los Angeles was first flown on 27 August 1924, and after completing flight trials began the transatlantic delivery flight on 12 October under the command of Hugo Eckener, arriving at the US Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey, after an 81-hour flight of 4,229 nautical miles (7,832 km; 4,867 mi).The airship was commissioned into the US Navy on 25 November 1924 at Anacostia, D.C. with Lieutenant Commander Maurice R. Pierce in command. On its arrival in the United States, its lifting gas was changed from hydrogen to helium, which reduced payload but improved safety. At the same time the airship was fitted with equipment to recover water from the exhaust gases for use as ballast to compensate for the loss of weight as fuel was consumed, so avoiding the necessity to vent scarce helium to maintain neutral buoyancy.

The airship went on to log a total of 4,398 hours of flight, covering a distance of 172,400 nautical miles (319,300 km; 198,400 mi). Long-distance flights included return flights to Panama, Costa Rica and Bermuda. It served as an observatory and experimental platform, as well as a training ship for other airships.

On 25 August 1927, while Los Angeles was tethered at the Lakehurst high mast, a gust of wind caught her tail and lifted it into colder, denser air that was just above the airship. This caused the tail to lift higher. The crew on board tried to compensate by climbing up the keel toward the rising tail, but could not stop the ship from reaching an angle of 85 degrees, before it descended. The ship suffered only slight damage and was able to fly the next day.

In 1929, Los Angeles was used to test the trapeze system developed by the US Navy to launch and recover fixed wing aircraft from rigid airships. The tests were a success and the later purpose-built Akron-class airships were fitted with this system. The temporary system was removed from Los Angeles, which never carried any aircraft on operational flights. On 31 January 1930, Los Angeles also tested the launching of a glider over Lakehurst, New Jersey.

On 25 May 1932, Los Angeles participated in a demonstration of photophone technology. Floating over the General Electric plant in Schenectady, New York, the crew of the ship engaged in an on-air conversation with a WGY radio announcer using a beam of light.[8]

As the terms under which the Allies permitted the United States to have Los Angeles restricted its use to commercial and experimental purposes only, when the U.S. Navy wanted to use the airship in a fleet problem in 1931 permission had to be obtained from the Allied Control Commission. Los Angeles took part in Fleet Problems XII (1931) and XIII (1932), although as was the case with all U.S. Navy rigid airships, demonstrated no particular benefit to the fleet.

Los Angeles was decommissioned in 1932 as an economy measure, but was recommissioned after the crash of USS Akron in April 1933. She flew for a few more years and then retired to her Lakehurst hangar where she remained until 1939, when the airship was struck off the Navy list and was dismantled in her hangar. Los Angeles was the Navy's longest serving rigid airship. Unlike Shenandoah, Akron, and Macon, the German-built Los Angeles was the only Navy rigid airship which did not meet a disastrous end.

Vought UO-1 observation airplane Parked at an airfield 1929. This airplane has been equipped for hook-on experiments with USS Los Angeles ZR-3

Vought UO-1 observation airplane Attached to the trapeze of USS Los Angeles ZR-3 during mating experiments in the airship hangar at Naval Air Station Lakehurst New Jersey

USS Akron (ZRS-4)

USS Akron (ZRS-4) was a helium-filled rigid airship of the U.S. Navy, the lead ship of her class, which operated between September 1931 and April 1933. She was the world's first purpose-built flying aircraft carrier, carrying F9C Sparrowhawk fighter planes, which could be launched and recovered while she was in flight. With an overall length of 785 ft (239 m), Akron and her sister ship Macon were among the largest flying objects ever built. Although LZ 129 Hindenburg and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II were some 18 ft (5.5 m) longer and slightly more voluminous, the two German airships were filled with hydrogen and so the US Navy craft still holds the world record for helium-filled airships.

Akron was destroyed in a thunderstorm off the coast of New Jersey on the morning of 4 April 1933, killing 73 of the 76 crewmen and passengers. The accident involved the greatest loss of life in any airship crash.

Technical description

The airship's skeleton was built of the new lightweight alloy duralumin 17-SRT. The frame introduced several novel features compared with traditional Zeppelin designs. Rather than being single-girder diamond trusses with radial wire bracing, the main rings of Akron were self-supporting deep frames: triangular Warren trusses 'curled' round to form a ring. Though much heavier than conventional rings, the deep rings promised to be much stronger, a significant attraction to the navy after the in-flight break up of the earlier conventional airships R38/ZR-2 and ZR-1 Shenandoah. The inherent strength of these frames allowed the chief designer, Karl Arnstein, to dispense with the internal cruciform structure used by Zeppelin to support the fins of their ships. Instead, the fins of Akron were cantilevered: mounted entirely externally to the main structure. Graf Zeppelin, Graf Zeppelin II, and Hindenburg used a supplementary axial keel along the hull centerline. However, the Akron used three keels, one running along the top of the hull and one each side, 45 degrees up from the lower centreline. Each keel provided a walkway running almost the entire length of the ship. The electric and telephone wiring, control cables, 110 fuel tanks, 44 water ballast bags, 8 engine rooms, engines, transmissions, and water-recovery devices were placed along the lower keels. Helium, instead of flammable hydrogen, allowed the engines to be placed inside the hull, improving streamlining. A generator room, with 2 Westinghouse d.c. generators powered by a 30-h.p. internal combustion engine, was forward of the No. 7 engine room.:36,187–197

The main rings were spaced at 22.5 m (74 ft) and between each pair were three intermediate rings of lighter construction. In keeping with conventional practice, 'station numbers' on the airship were measured in meters from zero at the rudder post, positive forward and negative aft. Thus the tip of the tail was at station −23.75 and the nose mooring spindle was at station 210.75. Each ring frame formed a polygon with 36 corners and these (and their associated longitudinal girders) were numbered from 1 (at the bottom centre) to 18 (at the top centre) port and starboard.Thus a position on the hull could be referred to, for example, as "6 port at station 102.5" (the number 1 engine room).

While Germany, France and Britain used goldbeater's skin to gas-proof their gasbags, Akron used Goodyear Tire and Rubber's rubberised cotton, heavier but much cheaper and more durable. Half the gas cells used an experimental cotton-based fabric impregnated with a gelatin-latex compound. This was more expensive than the rubberised cotton but lighter than goldbeater's skin. It was so successful that all the gasbags of Macon were made from it. There were 12 gas cells, numbered 0 to XI, using Roman numerals and starting from the tail. While the 'air volume' of the hull was 7,401,260 cu ft (209,580 m3), the total volume of the gas cells at 100 percent fill was 6,850,000 cu ft (194,000 m3). At a normal 95 percent fill with helium of standard purity, the 6,500,000 cu ft (180,000 m3) of gas would yield a gross lift of 403,000 lb (183,000 kg). Given a structure deadweight of 242,356 lb (109,931 kg), this gives a useful lift of 160,644 lb (72,867 kg) available for fuel, lubricants, ballast, crew, supplies and military load (including the skyhook airplanes)

Eight Maybach VL II 560 hp (420 kW) gasoline engines were mounted inside the hull. Each engine turned a two-bladed, 16 ft 4 in (4.98 m) diameter, fixed pitch, wooden propeller via a driveshaft and bevel gearing which allowed the propeller to swivel from the vertical plane to the horizontal. With the engines' ability to reverse, this allowed thrust to be applied forward, aft, up or down. It appears from photographs that the four propellers on each side were contra-rotating, each one turning the opposite way to the one ahead of it. Thus it would appear that the designers were aware that running the propellers in the air disturbed by the one ahead was not ideal. While the external engine pods of other airships allowed the thrust lines to be staggered, placing all four engine rooms on each side of the ship along the lower keel resulted in Akron's propellers all being in line. This was to prove problematical in service, inducing considerable vibration, especially noticeable in the emergency control position in the lower fin. By 1933, Akron had two of her propellers replaced by more advanced, ground-adjustable, three-bladed, metal propellers. These promised a performance increase and were adopted as standard for Macon.

The outer cover was of cotton cloth, treated with four coats of clear and two coats of aluminum pigmented cellulose dope. The total area of the skin was 330,000 sq ft (31,000 m2) and it weighed, after doping, 113,000 lb (51,000 kg).

The prominent dark vertical bands on the hull were condensers of the system designed to recover water from the engines' exhaust for buoyancy compensation. In-flight fuel consumption continuously reduces an airship's weight and changes in the temperature of the lifting gas can do the same. Normally, expensive helium has to be valved off to compensate and any way of avoiding this is desirable. In theory, a water recovery system such as this can produce 1 lb of ballast water for every lb of fuel burned, though this is unlikely to be achieved in practice.

Akron could carry up to 20,700 US gal (78,000 L) of gasoline (126,000 lb (57,000 kg)) in 110 separate tanks which were distributed along the lower keels to preserve the ship's trim, giving her a normal range of 5,940 nmi (6,840 mi; 11,000 km) at cruising speed. Theoretical maximum ballast water capacity was 223,000 lb (101,000 kg) in 44 bags, again distributed along her length, though normal ballast load at unmasting was 20,000 lb (9,100 kg).

The heart of the ship, and her sole reason for existing, was the airplane hangar and trapeze system. Aft of the control car, in bay VII, between frames 125 and 141.25, was a compartment large enough to accommodate up to five F9C Sparrowhawk airplanes. However, two structural girders partially obstructed Akron's aftmost hangar bays, limiting its capacity to three airplanes (one in each forward corner of the hangar and one on the trapeze). A modification to remove this design flaw was pending at the time of the ship's loss.

The F9C was not the ideal choice, being designed as a 'conventional' carrier-borne fighter. It was heavily built to withstand carrier landings, downward visibility was not very good and it initially lacked an effective radio. But the primary role of Akron's airplanes was long-range naval scouting. What was actually needed was a stable, fast, lightweight scouting airplane with a long range, but none existed capable of fitting between the structural members and into the airship's hangar, as the F9C could.

The trapeze was lowered through the T-shaped door in the bottom of the ship and into the slipstream, with an airplane attached to the crossbar by the 'skyhook' above its top wing, its pilot on board and its engine running. The pilot tripped the hook and the airplane fell away from the ship. On his return, he positioned himself beneath the trapeze and climbed up until he could fly his skyhook onto the crossbar, at which point it automatically latched shut. Now, with the engine idling, the trapeze and airplane were raised into the hangar, the pilot cutting his engine as he passed through the door. Once inside, the airplane was transferred from the trapeze to a trolley, running on an overhead 'monorail' system by which it could be shunted into one of the four corners of the hangar to be refueled and re-armed. Having a single trapeze raised two problems: it limited the rate at which airplanes could be launched and recovered and any fault in the trapeze would leave any airborne scouts with nowhere to land. The solution was a second, fixed trapeze permanently rigged further aft along the bottom of the ship at station 102.5 and known as the 'perch'. By 1933 a perch was fitted and in use. Three more perches were planned (at stations 57.5, 80 and 147.5) but these were never fitted.

Akron revived an idea used, and eventually rejected, by the German Navy zeppelins during World War I: the spähkorb or 'spy basket'.The "angel basket" or "sub-cloud observation car", allowed the airship to remain hidden in a cloud layer, while still observing the enemy below. The small car, rather like an airplane fuselage without wings, could be lowered on a 1000 foot long cable. The observer on board communicated with the ship by telephone. In practice, the device was unstable, almost looping over the airship during its only test flight.

During the design stage, in 1929, the navy requested an alteration to the fins. It was considered desirable for the bottom of the lower fin to be visible from the control car. Charles E. Rosendahl had witnessed, from the control room, Graf Zeppelin almost snagging her fin on high-tension power lines during her heavy take off into an unsuspected but very marked temperature inversion from Mines Field, Los Angeles at the start of the last leg of her round-the-world flight earlier that year. The design change would also allow direct vision between the main control car and the emergency control position in the lower fin. The control car was moved 8 ft (2.4 m) aft and all the fins were shortened and deepened. The leading edge root of the fins no longer coincided with a main (deep) ring and instead the foremost attachment was now to an intermediate ring at frame 28.75. This achieved the required visibility, improved low-speed controllability, due to the increased span of the control surfaces, and simplified stress calculations, by reducing the number of fin attachment points. The designers and the navy's inspectors, led by the very experienced Charles P Burgess, were entirely satisfied with the revised stress calculations. However, this alteration has been the subject of much criticism as an "inherent defect" in the design and is often alleged to have been a major factor in the loss of Akron's sister ship Macon.

Construction and commissioning

Construction of ZRS-4 was begun on 31 October 1929 at the Goodyear Airdock in Akron, Ohio by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation.Because she was larger than any airship previously built in the USA, a special hangar was constructed Chief Designer Karl Arnstein and a team of experienced German airship engineers instructed and supported design and construction of both U.S. Navy airships USS Akron and USS Macon.

On 7 November 1929, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, the Chief of the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics, drove the "golden rivet" into the main ring of "ZRS4". Erection of the hull sections began in March 1930. Secretary of the Navy Charles Francis Adams chose the name Akron (for the city near where she was being built), and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Ernest Lee Jahncke announced it in May 1930.

On 8 August 1931, Akron was launched (floated free of the hangar floor) and christened by First Lady Lou Henry Hoover, the wife of the President of the United States, Herbert Clark Hoover. The maiden flight of Akron took place around Cleveland on the afternoon of 23 September with Secretary of the Navy Adams and Rear Admiral Moffett on board. The airship made ten trial flights, including a 2000 mile journey, over 48 hours, to St. Louis, Chicago, and Milwaukee. On 21 October Akron left the Goodyear Zeppelin Air Dock for the Naval Air Station (NAS), with Lieutenant Commander Charles E. Rosendahl in command, arriving the next day. On Navy Day, 27 October 1931, the Akron was commissioned as a Navy vessel.

History of service

On 2 November 1931, Akron departed on her first cruise down the eastern seaboard to Washington, D.C. On 3 November the "Akron" took to the air with 207 persons on board. This demonstration was to prove that in an emergency airships could provide limited but high speed airlift of troops to outlying possessions. Over the weeks that followed, some 300 hours aloft were logged in a series of flights, including a 46-hour endurance flight to Mobile, Alabama, and back. The return leg of the trip was made via the valleys of the Mississippi River and the Ohio River.

On the morning of 9 January 1932, Akron departed from Lakehurst to work with the Scouting Fleet on a search exercise. Proceeding to the coast of North Carolina, Akron headed out over the Atlantic where she was assigned to find a group of destroyers bound for Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. Once these were located, the airship was to shadow them and report their movements. Leaving the coast of North Carolina at about 7:21 on the morning of 10 January, the airship proceeded south, but bad weather prevented sighting the destroyers (contact with them was missed at 12:40 EST, although their crews had sighted Akron) and eventually shaped a course toward the Bahamas by late afternoon. Heading northwesterly into the night, Akron then changed course shortly before midnight and proceeded to the southeast. Ultimately, at 9:08 am on 11 January, the airship succeeded in spotting the light cruiser USS Raleigh and 12 destroyers, positively identifying them on the eastern horizon two minutes later. Sighting a second group of destroyers shortly thereafter, Akron was released from the evaluation about 10:00 a.m., having achieved a "qualified success" in the initial test with the Scouting Fleet, but the performance could have been better with radio detection finding equipment, and scout planes.

As the historian Richard K Smith wrote in his definitive study, The Airships Akron and Macon, "...consideration given to the weather, duration of flight, a track of more than 3,000 mi (4,800 km) flown, her material deficiencies, and the rudimentary character of aerial navigation at that date, the Akron's performance was remarkable. There was not a military airplane in the world in 1932 which could have given the same performance, operating from the same base.

Akron was to have taken part in Fleet Problem XIII, but an accident at Lakehurst on 22 February 1932 prevented her participation. While the airship was being taken from her hangar, the tail came loose from her moorings, was caught by the wind, and struck the ground. The heaviest damage was confined to the lower fin area, which required repair. Also, ground handling fittings had been torn from the main frame, necessitating further repairs. Akron was not certified as airworthy again until later in the spring. Her next operation took place on 28 April, when she made a nine-hour flight with Rear Admiral Moffett and Secretary of the Navy Adams aboard.

As a result of this accident, a turntable with a walking beam on tracks powered by electric mine locomotives was developed to secure the tail and turn the ship even in high winds so that she could be pulled into the massive hangar at Lakehurst

Soon after returning to Lakehurst to disembark her distinguished passengers, Akron took off again to conduct a test of the "spy basket"—something like a small airplane fuselage suspended beneath the airship that would enable an observer to serve as the ship's "eyes" below the clouds while the ship herself remained out of sight above them. The first time the basket was tried (with sandbags aboard instead of a man), it oscillated so violently that it put the whole ship in danger. The basket proved "frighteningly unstable", swooping from one side of the airship to the other before the startled gaze of Akron's officers and men and reaching as high as the ship's equator.Though it was later improved by adding a ventral stabilizing fin, the spybasket was never used again.

Akron and Macon (which was still under construction) were regarded as potential "flying aircraft carriers", carrying parasite fighters for reconnaissance. On 3 May 1932, Akron cruised over the coast of New Jersey with Rear Admiral George C. Day, and the Board of Inspection and Survey, on board, and for the first time tested the "trapeze" installation for in-flight handling of aircraft. The aviators who carried out those historic "landings"—first with a Consolidated N2Y trainer and then with the prototype Curtiss XF9C-1 Sparrowhawk—were Lieutenant D. Ward Harrigan and Lieutenant Howard L. Young. The following day, Akron carried out another demonstration flight, this time with members of the House Committee on Naval Affairs on board; this time, Lieutenants Harrigan and Young gave the lawmakers a demonstration of Akron's aircraft hook-on ability.

Following the conclusion of those trial flights, Akron departed from Lakehurst, New Jersey on 8 May 1932, for the American west coast. The airship proceeded down the eastern seaboard to Georgia and then across the southern gulf states, continuing over Texas and Arizona. En route to Sunnyvale, California, Akron reached Camp Kearny in San Diego, on the morning of 11 May and attempted to moor. Since neither trained ground handlers nor specialized mooring equipment were present, the landing at Camp Kearny was fraught with danger. By the time the crew started the evaluation, the helium gas had been warmed by sunlight, increasing lift. Lightened by 40 short tons (36 t), the amount of fuel spent during the transcontinental trip, Akron was now uncontrollably light.

The mooring cable was cut to avert a catastrophic nose-stand by the errant airship which floated upward. Most of the mooring crew—predominantly "boot" seamen from the Naval Training Station San Diego—released their lines although four did not. One let go at about 15 ft (4.6 m) and suffered a broken arm while the three others were carried further aloft. Of these Aviation Carpenter's Mate 3rd Class Robert H. Edsall and Apprentice Seaman Nigel M. Henton soon plunged to their deaths while Apprentice Seaman C. M. "Bud" Cowart held on to his line and then secured himself to it before being hoisted on board the airship an hour later. Akron moored at Camp Kearny later that day before proceeding to Sunnyvale, California. Footage from the accident appears in the film Encounters with Disaster, released in 1979 and produced by Sun Classic Pictures.

Over the weeks that followed, Akron "showed the flag" on the West Coast of the United States, ranging as far north as the Canada–US border before returning south in time to exercise once more with the Scouting Fleet. Serving as part of the "Green Force", the Akron attempted to locate the "White Force". Although opposed by Vought O2U Corsair floatplanes from "enemy" warships, the airship located the opposing forces in just 22 hours, a fact not lost upon some of the participants in the exercise in subsequent critiques.

In need of repairs, Akron departed from Sunnyvale on 11 June 1932 bound for Lakehurst, New Jersey, on a return trip that was sprinkled with difficulties, mostly because of unfavorable weather, and having to fly at pressure height while crossing the mountains. Akron arrived on 15 June after a "long and sometimes harrowing" aerial voyage.

Akron next underwent a period of voyage repairs before taking part in July in a search for Curlew, a yacht which had failed to reach port at the end of a race to the island of Bermuda. The yacht was later discovered safe off Nantucket. She then resumed operations capturing aircraft on the "trapeze" equipment. Admiral Moffett again boarded Akron on 20 July, but the next day left the airship in one of her N2Y-1s which took him back to Lakehurst after a severe storm had delayed the airship's own return to base.

In need of repairs, Akron departed from Sunnyvale on 11 June 1932 bound for Lakehurst, New Jersey, on a return trip that was sprinkled with difficulties, mostly because of unfavorable weather, and having to fly at pressure height while crossing the mountains. Akron arrived on 15 June after a "long and sometimes harrowing" aerial voyage.

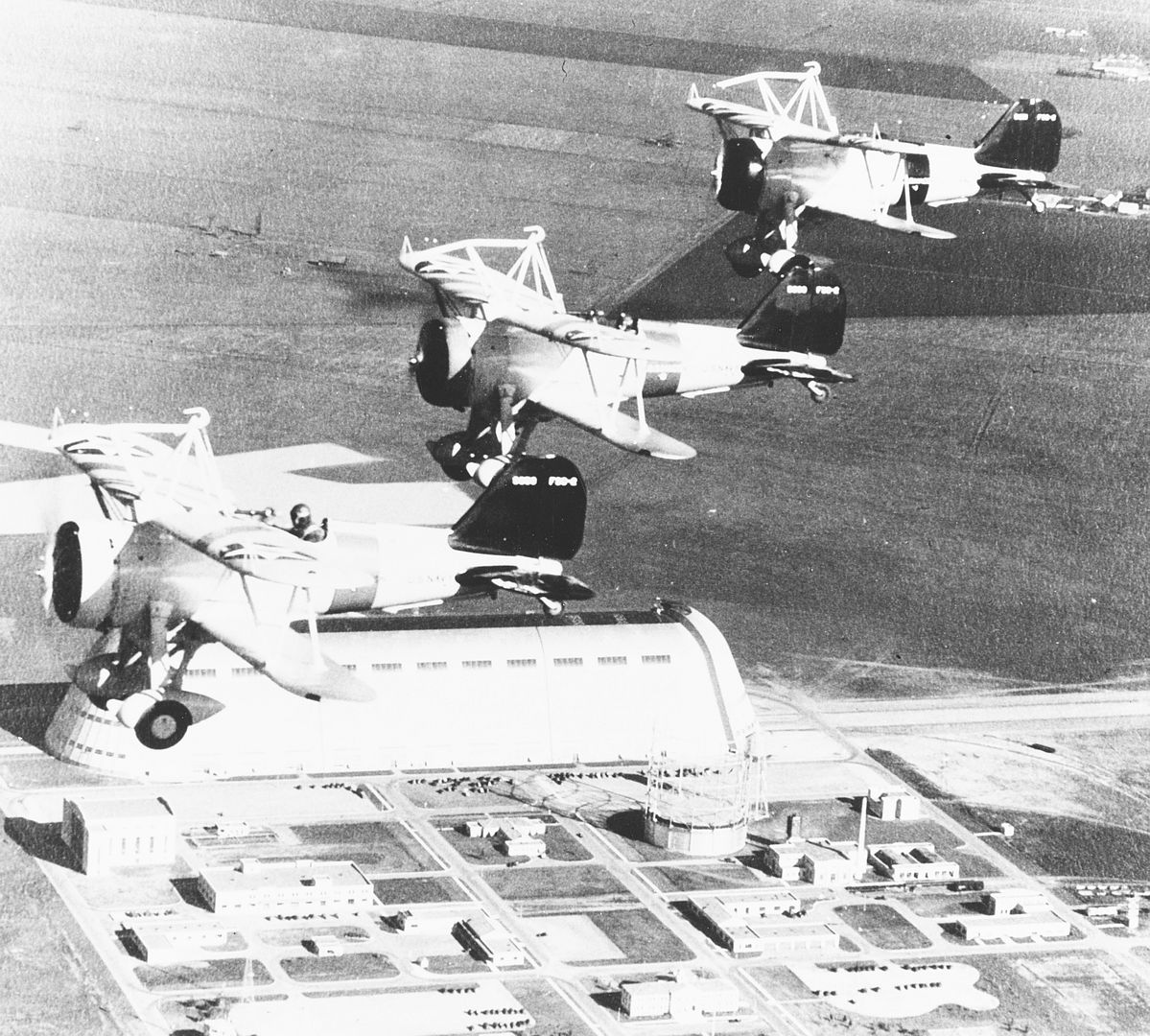

Akron entered a new phase of her career that summer of 1932, engaging in intense experimentation with the revolutionary "trapeze" and a full complement of F9C-2s. A key element of the entrance into that new phase was a new commanding officer, Commander Alger Dresel.

Another accident hampered training on 22 August when Akron's tail fin became fouled by a beam in Lakehurst's massive Hangar No 1 after a premature order to commence towing the ship out of the mooring circle. Nevertheless, rapid repairs enabled eight more flights over the Atlantic during the last three months of 1932. These operations involved intensive work with the trapeze and the F9C-2s, as well as the drilling of lookouts and gun crews.

Among the tasks undertaken were the maintenance of two aircraft patrolling and scouting on Akron's flanks. During a seven-hour period on 18 November 1932, the airship and a trio of planes searched a sector 100 mi wide.

After local operations out of Lakehurst for the remainder of 1932, Akron was ready to resume operations with the fleet. On the afternoon of 3 January 1933, Commander Frank C. McCord relieved Commander Dresel as commanding officer, the latter becoming the first commanding officer of Akron's sister ship Macon, whose construction was almost complete. Within hours, Akron headed south down the eastern seaboard toward Florida where, after refueling at the Naval Reserve Aviation Base, Opa-locka, Florida, near Miami, the next day proceeded to Guantánamo Bay for an inspection of base sites. At this time the N2Y-1s were used to provide aerial "taxi" service to ferry members of the inspection party back and forth.

Soon thereafter, Akron returned to Lakehurst for local operations which were interrupted by a two-week overhaul and poor weather. In March, she carried out intensive training with an aviation unit of F9C-2s, honing hook-on skills. During the course of these operations, an overfly of Washington DC was made 4 March 1933, the day Franklin D. Roosevelt first took the oath of office as President of the United States.

On 11 March, Akron departed Lakehurst bound for Panama stopping briefly en route at Opa-locka before proceeding on to Balboa where an inspection party looked over a potential air base site. While returning northward, the airship paused at Opa-locka again for local operations exercising gun crews, with the N2Y-1s serving as targets, before getting underway for Lakehurst on 22 March.

Loss

On the evening of 3 April 1933, Akron cast off from the mooring mast to operate along the coast of New England, assisting in the calibration of radio direction finder stations. Rear Admiral Moffett was again on board along with his aide, Commander Henry Barton Cecil, Commander Fred T. Berry, the commanding officer of NAS Lakehurst, and Lieutenant Colonel Alfred F. Masury, U.S. Army Reserve, a guest of the admiral, the vice-president of Mack Trucks, and a strong proponent of the potential civilian uses of rigid airships.

After casting off at 1928, Akron soon encountered fog and then severe weather, which did not improve when the airship passed over Barnegat Light, New Jersey, at 2200. According to Richard Smith, "Unknown to the men on board the Akron, they were flying ahead of one of the most violent stormfronts to sweep the North Atlantic States in ten years. It would soon envelop them." Enveloped in fog, increased lightning and heavy rain, it became extremely turbulent at 0015. The Akron began a rapid nose-down descent, reaching 1100 feet while still falling. Ballast was dumped, which stabilized the ship at 700 feet, and climbed back to 1600 feet cruising altitude. Then a second violent descent sent the Akron downwards at 14 feet per second. "Landing stations" alerted the crew, as the ship descended tail-down. The lower fin struck the sea, water entered the fin, and the stern was dragged under. The engines pulled the ship into a nose-high attitude, then the Akron stalled, and crashed into the sea.

Akron broke up rapidly and sank in the stormy Atlantic. The crew of the nearby German merchant ship Phoebus saw lights descending toward the ocean at about 12:23 a.m. and altered course to starboard to investigate, with her captain believing that he was witnessing an airplane crash. At 12:55 a.m., Wiley was pulled from the water while the ship's boat picked up three more men: Chief Radioman Robert W. Copeland, Boatswain's Mate Second Class Richard E. Deal, and Aviation Metalsmith Second Class Moody E. Erwin. Despite artificial respiration, Copeland never regained consciousness, and he died aboard Phoebus.

Although the German sailors spotted four or five other men in the water, they did not know their ship had chanced upon the crash of Akron until Lt. Commander Wiley regained consciousness half an hour after being rescued. The crew of Phoebus combed the ocean in boats for over five hours in a fruitless search for more survivors. The Navy blimp J-3—sent out to join the search—also crashed, with the loss of two men.

The U.S. Coast Guard cutter Tucker—the first American vessel on the scene—arrived at 6:00 a.m., taking the airship's survivors and the body of Copeland on board. Among the other ships combing the area for survivors were the heavy cruiser Portland, the destroyer Cole, the Coast Guard cutter Mojave, and the Coast Guard destroyers McDougal and Hunt, as well as two Coast Guard aircraft. The fishing vessel Grace F from Gloucester, Massachusetts, also assisted in the search, using her seining gear in an effort to recover bodies.

Most casualties had been caused by drowning and hypothermia, since the crew had not been issued life jackets, and there had not been time to deploy the single life raft. The accident left 73 dead, and only three survivors. Wiley, standing next to the two other survivors, gave a brief account on 6 April.

Akron's loss spelled the beginning of the end for the rigid airship in the US Navy, especially since one of her leading proponents, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, was among the dead. President Roosevelt said, "The loss of the Akron with her crew of gallant officers and men is a national disaster. I grieve with the Nation and especially with the wives and families of the men who were lost. Ships can be replaced, but the Nation can ill afford to lose such men as Rear Admiral William A. Moffett and his shipmates who died with him upholding to the end the finest traditions of the United States Navy." The loss of the Akron was the largest loss of life in any airship crash.

Macon and other airships received life jackets to avert a repetition of this tragedy. When Macon was damaged in a storm in 1935 and subsequently sank after landing in the sea, 70 of the 72 crew were saved.

The songwriter Bob Miller wrote and recorded a song, "The Crash of the Akron", within one day of the disaster.

In the summer of 2003, the US submarine NR-1 surveyed the wreck site and performed sonar imaging of the Akron's girders.

General characteristics

Crew: 60

Length: 785 ft (239 m)

Diameter: 133 ft 4 in (40 m)

Height: 146 ft (45 m)

Volume: 7,401,260 cu ft (209,580 m3)

Useful lift: 152,644 lb (69,238 kg)

Powerplant: 8 × Maybach VL II 12-cyl water-cooled, inline engines, 560 hp (420 kW) each

Propellers: 2-bladed fixed-pitch, rotatable wooden propellers

Performance

Maximum speed: 69 kn (79 mph, 128 km/h)

Cruise speed: 55 kn (63 mph, 102 km/h)

Range: 5,940 nmi (6,840 mi, 11,000 km) at 55 knots (102 km/h; 63 mph)

Armament

Guns: 8 x.30-cal machine guns

Consolidated N2Y-1 training plane Bureau 8604 Photographed while serving as hook-on familiarization trainer for USS Akron ZRS-4 1932.

Curtiss F9C-2 Sparrowhawk fighter Bureau 9059 Inside the airplane hangar of USS Akron ZRS-4 1932.

USS Akron ZRS-4 Launches a Consolidated N2Y-1 training plane Bureau A8604 during flight tests near Naval Air Station Lakehurst New Jersey 4 May 1932.

USS Macon (ZRS-5)

USS Macon (ZRS-5) was a rigid airship built and operated by the United States Navy for scouting and served as a "flying aircraft carrier", designed to carry biplane parasite aircraft, five single-seat Curtiss F9C Sparrowhawk for scouting or two-seat Fleet N2Y-1 for training. In service for less than two years, in 1935 the Macon was damaged in a storm and lost off California's Big Sur coast, though most of the crew were saved. The wreckage is listed as the USS Macon Airship Remains on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places.

Less than 20 ft (6.1 m) shorter than Hindenburg, both Macon and her sister ship Akron were among the largest flying objects in the world in terms of length and volume. Although both of the hydrogen-filled, Zeppelin-built Hindenburg and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II were longer, the two American-built sister naval airships still hold the world record for helium-filled rigid airships.

Construction

USS Macon was built at the Goodyear Airdock in Springfield Township, Ohio by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation. Because this was by far the biggest airship ever to be built in America, a team of experienced German airship engineers—led by Chief Designer Karl Arnstein—instructed and supported design and construction of both the U.S. Navy airships Akron and Macon.

Macon had a structured duraluminum hull with three interior keels.The airship was kept aloft by 12 helium-filled gas cells made from gelatin-latex fabric. Inside the hull, the ship had eight German-made Maybach VL II 12-cylinder, 560 hp (418 kW) gasoline-powered engines that drove outside propellers. The propellers could be rotated down or backwards, providing an early form of thrust vectoring to control the ship during takeoff and landings. The rows of slots in the hull above each engine were part of a system to condense out the water vapor from the engine exhaust gases for use as buoyancy compensation ballast to compensate for the loss of weight as fuel was consumed.

Service history

Macon was christened on 11 March 1933, by Jeanette Whitton Moffett, wife of Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics. The airship was named after the city of Macon, Georgia, which was the largest city in the Congressional district of Carl Vinson, then the chairman of the U.S. House of Representatives' Committee on Naval Affairs.

The airship first flew on 21 April, aloft over northern Ohio for nearly 13 hours with 105 aboard, just over a fortnight after the loss of Akron in which Admiral Moffett and 72 others were killed. Macon was commissioned into the U.S. Navy on 23 June 1933, with Commander Alger H. Dresel in command.

On 24 June 1933, Macon left Goodyear's field for Naval Air Station (NAS) Lakehurst, New Jersey, where the new airship was based for the summer while undergoing a series of training flights.

Macon had a far more productive career than Akron, which crashed on 4 April 1933. The commanders of Macon developed the doctrine and techniques of using her on-board aircraft for scouting while the airship remained out of sight of the opposing forces during exercises.[10] Macon participated in several fleet exercises, though the men who framed and conducted the exercises lacked an understanding of the airship's capabilities and weaknesses. It became standard practice to remove the landing gear of the Sparrowhawks while aboard the airship and then replace it with a fuel tank, thus giving the aircraft 30 percent more range.

Macon first operated aircraft on 6 July 1933 during trial flights out of Lakehurst, New Jersey. The planes were stored in bays inside the hull and were launched and retrieved using a trapeze.

The airship left the East Coast on 12 October 1933, on a transcontinental flight to her new permanent homebase at NAS Sunnyvale (now Moffett Federal Airfield) near San Francisco in Santa Clara County, California.

In 1934, two two-seat Waco UBF XJW-1 biplanes equipped with skyhooks were delivered to USS Macon.

In June 1934, Lieutenant Commander Herbert V. Wiley took command of the airship, and shortly afterwards he surprised President Roosevelt (and the Navy) when Macon searched for and located the heavy cruiser Houston, which was then carrying the president back from a trip to Hawaii. Newspapers were dropped to the President on the ship, and the following communications were sent back to the airship: "from Houston: 1519 The President compliments you and your planes on your fine performance and excellent navigation 1210 and 1519 Well Done and thank you for the papers the President 1245." The commander of the Fleet, Admiral Joseph M. Reeves, was upset about the matter: but the Commander of the Bureau of Aviation, Admiral Ernest J. King was not. Wiley, one of only three survivors of the crash of the Akron, was soon promoted to commander, served as the captain of the battleship West Virginia in the final two years of World War II, and then retired from the Navy in 1947 as a rear admiral.

Loss

On 20 April 1934, the Macon left Sunnyvale for a challenging cross continent flight east to Opa-locka, Florida. As with the Akron in 1932, Macon had to fly at or above pressure height when crossing the mountains, especially over Dragoon Pass at an elevation of 4,629 ft (1,411 m). Then, in the West Texas heat, the sun raised the helium temperature, and the consequent expanding gas was automatically venting as the airship flew along at pressure height once again. Full engine power was required as the weather became turbulent. Following a severe gust near Van Horn, Texas, a diagonal girder in frame 17.5, near the fin junction, failed, followed soon by a second diagonal girder. Rapid damage control, led by Chief Boatswain's Mate Robert J. Davis, repaired the girders within a half hour. Macon completed the rest of the journey safely, mooring at Opa-locka on 22 April. More permanent repairs there took 9 days. However, the addition of duralumin channels, to reinforce frame 17.5 at its junction with the upper fin, was not completed. Grounding the Macon, until these reinforcements were made, was considered unnecessary.

On 12 February 1935, the repair process was still incomplete when, returning to Sunnyvale from fleet maneuvers, Macon ran into a storm off Point Sur, California. During the storm, the ship was caught in a wind shear which caused structural failure of the unstrengthened ring (17.5) to which the upper tailfin was attached. The fin failed to the side and was carried away. Pieces of structure punctured the rear gas cells and caused gas leakage. The commander, acting rapidly and on fragmentary information, ordered an immediate and massive discharge of ballast. Control was lost and, tail heavy and with engines running full speed ahead, Macon rose past the pressure height of 2,800 ft (850 m), and kept rising until enough helium was vented to cancel the lift, reaching an altitude of 4,850 ft (1,480 m). The last SOS call from Commander Wiley stated "Will abandon ship as soon as we land on the water somewhere 20 miles off of Pt. Sur, probably 10 miles at sea." It took 20 minutes to descend and, settling gently into the sea, Macon sank off Monterey Bay. Only two crew members were lost thanks to the warm conditions and the introduction of life jackets and inflatable rafts after the Akron tragedy. Radioman 1st Class Ernest Edwin Dailey jumped ship while still too high above the ocean surface to survive the fall and Mess Attendant 1st Class Florentino Edquiba drowned while swimming back into the wreckage to try to retrieve personal belongings. An officer was rescued when Commander Wiley swam to his aid, an action for which he was later decorated. Sixty-four survivors were picked up by the cruiser Richmond, the cruiser Concord took 11 aboard and the cruiser Cincinnati saved six.

Eyewitness Dorsey A. Pulliam, serving aboard USS Colorado, wrote about the crash in a letter dated 13 February 1935:

Tuesday it was so rough, and with the rain, we had an awful time getting along. We had gunnery drill Tuesday and more fleet maneuvers. The Macon came out about 1 pm Tues. to maneuver with the fleet and to enter Frisco with us this morning. The Macon came out in the storm not knowing that she would never get back to land. The Macon circled high above the fleet all the afternoon, and about 6 o'clock, radio messages began coming in that the Macon had had casualties and would have to land. The C.C. of the fleet radioed all ships in company with us to go at full speed for the wreckage. The crew abandoned it as soon as it hit the water, and all were saved except two. There were 83 men in the crew. The wreckage sank within a few minutes after it hit the water. We lingered around the spot where it sank looking for any parts which might be floating around. The search lights on all ships were combing the waters all through the night. The crew to the Macon were floating around in rubber floats and almost froze to death. I had to read about the Akron disaster, but this one I witnessed. The commander Clay had just been transferred to the Macon from this ship. This may contradict with the papers, but this is straight. There was an explosion in the tail and they could not control it.

In another letter, dated 16 February 1935, he wrote:

I guess that you all read all about the wreck of the Macon. Well, the papers out here were full. I guess the Navy sunk about 3 million dollars there in about 20 minutes. The people will have to pay that back in taxes. It sure was a pity that the Macon had to sink. It sure was pretty sailing around when the sun was shining on it. There sure was plenty excitement on board here that night. Everybody was trying to see what had happened. When the thing hit the water, the gas caught on fire and burned almost all night on the surface of the water after the bulk of the wreckage had sank. The Macon was supposed to go to Hawaii in May. They had started fixing up a field for it.

Macon, after 50 flights since it was commissioned, was stricken from the Navy list on 26 February 1935. Subsequent airships for Navy use were of a nonrigid design.

Admiral David F. Sellers USN Commander in Chief U.S. Fleet In the control car of USS Macon ZRS-5 on 9 November 1934

Waco XJW-1 utility airplane USS Macon

Waco XJW-1 utility airplaneBureau 9521 Parked at Naval Air Station Moffett Field California circa 1934-1935

-

4 years agoSun Sep 05 2021, 08:13pmDuggy

Main AdminCurtiss F9C Sparrowhawk

Main AdminCurtiss F9C Sparrowhawk

Design and development

On 20 August 1929, off the coast of New Jersey, a biplane hooked itself to the bottom of a dirigible and was carried along by the larger craft. This was the second such incident. The “snapon, snapoff” experiment was accomplished by the Navy airship USS Los Angeles, under Lt. Com. Herbert Wiley, and a Navy biplane. The biplane, regulating its speed to that of the dirigible, flew close under the Los Angeles. A large hook had been attached to the middle of the top wing of the biplane, and from the bottom of the Los Angeles hung a U-shaped yoke. Maneuvering the ship under the dirigible, the plane pilot slipped the hook into the Los Angeles’ yoke and for 3 or 4 minutes the dirigible carried the biplane. The plane pilot, by a cord arrangement in his cabin, withdrew the hook from the yoke and flew clear of the dirigible.

Although designed as a pursuit plane or fighter, the Sparrowhawk's primary duty in service was reconnaissance, enabling the airships it served to search a much wider area of ocean. The Sparrowhawk was primarily chosen for service aboard the large rigid-framed airships Akron and Macon because of its small size (20.2 ft (6.2 m) long and with only a 25.5 ft (7.8 m) wingspan), though its weight, handling and range characteristics, and also downward visibility from the cockpit, were not ideal for its reconnaissance role.The theoretical maximum capacity of the airships' hangar was five aircraft, one in each hangar bay and one stored on the trapeze but, in the Akron, two structural girders obstructed the aft two hangar bays, limiting her to a maximum complement of three Sparrowhawks. A modification to remove this limitation was pending at the time of the airship's loss. Macon had no such limitation and she routinely carried four airplanes.

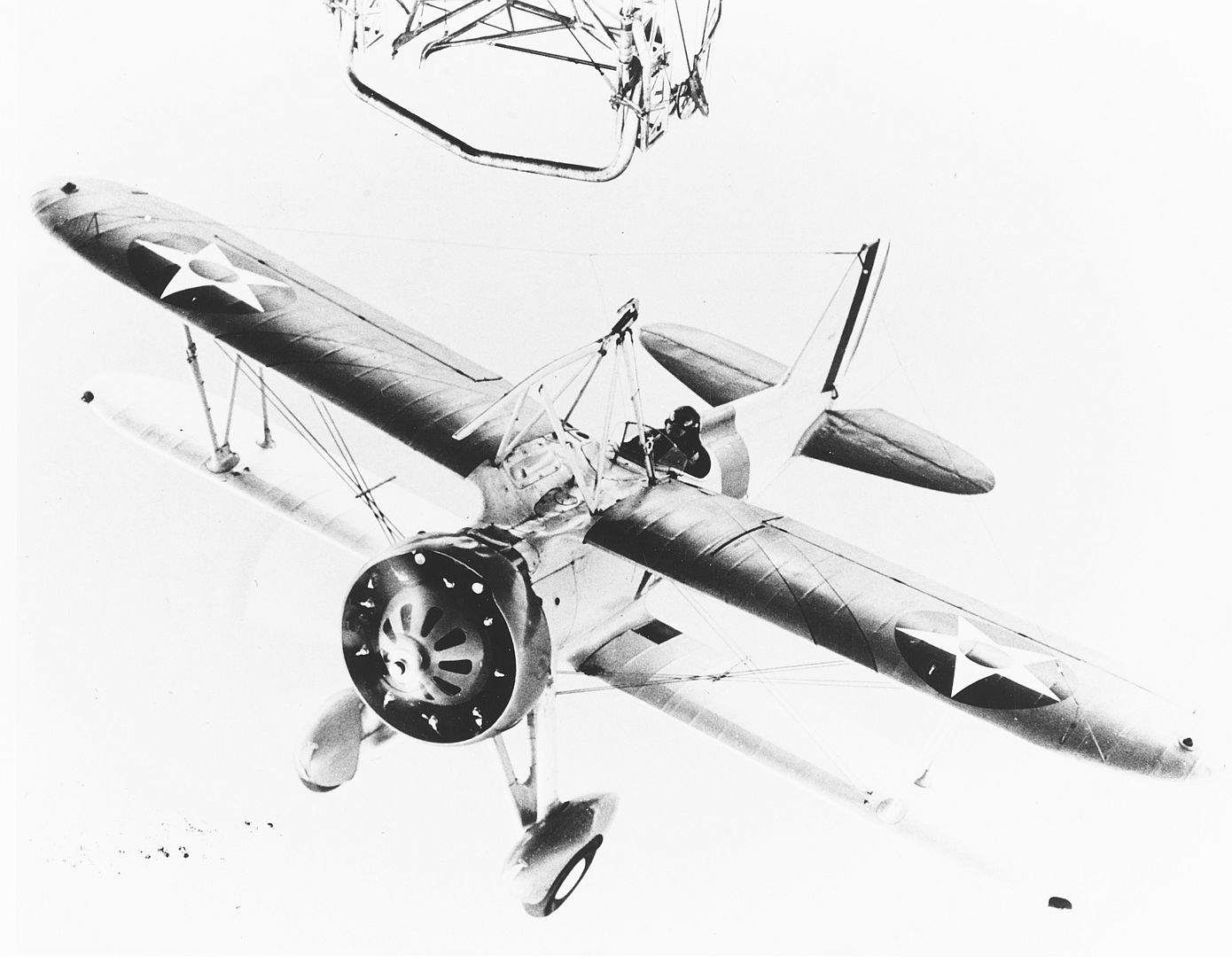

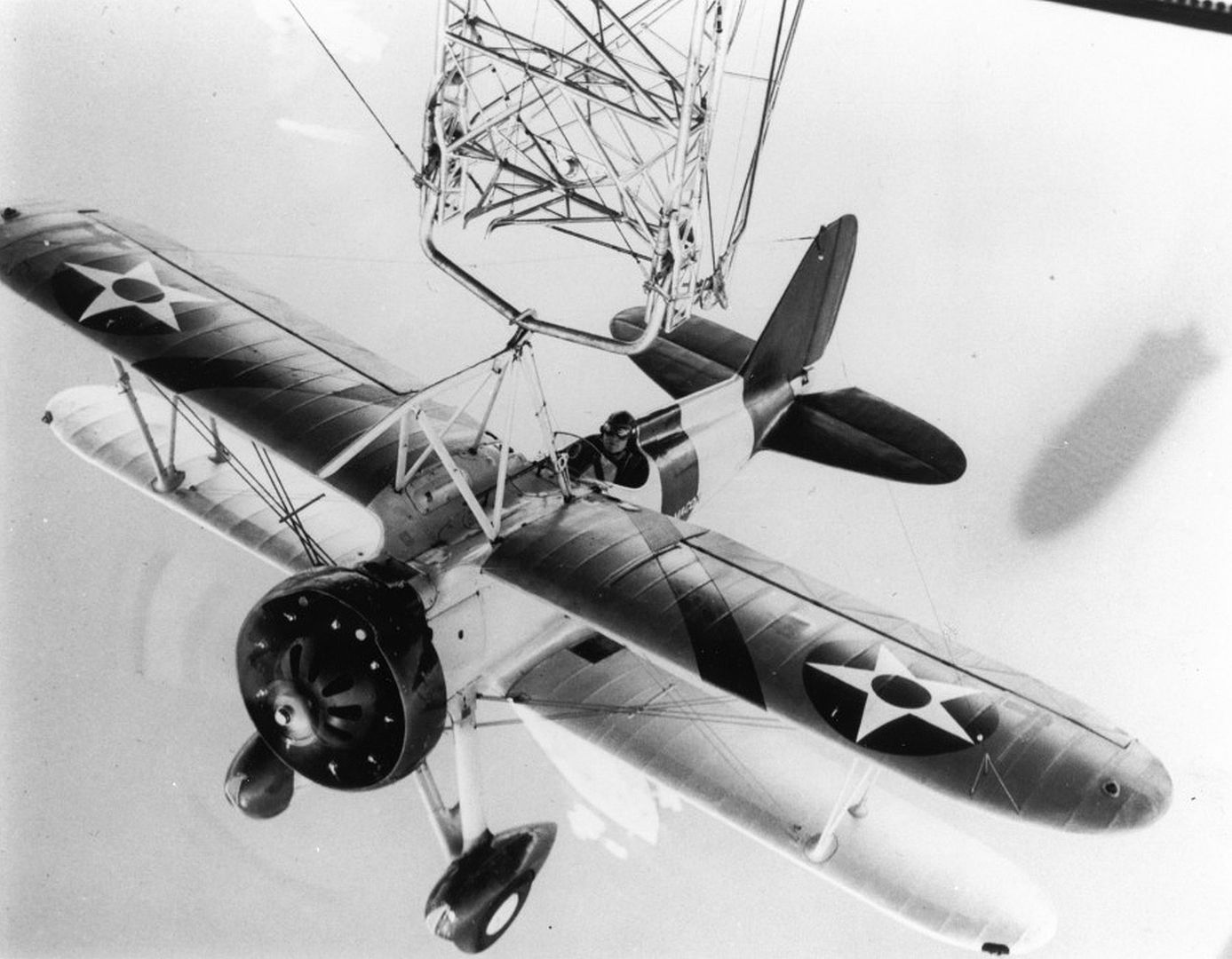

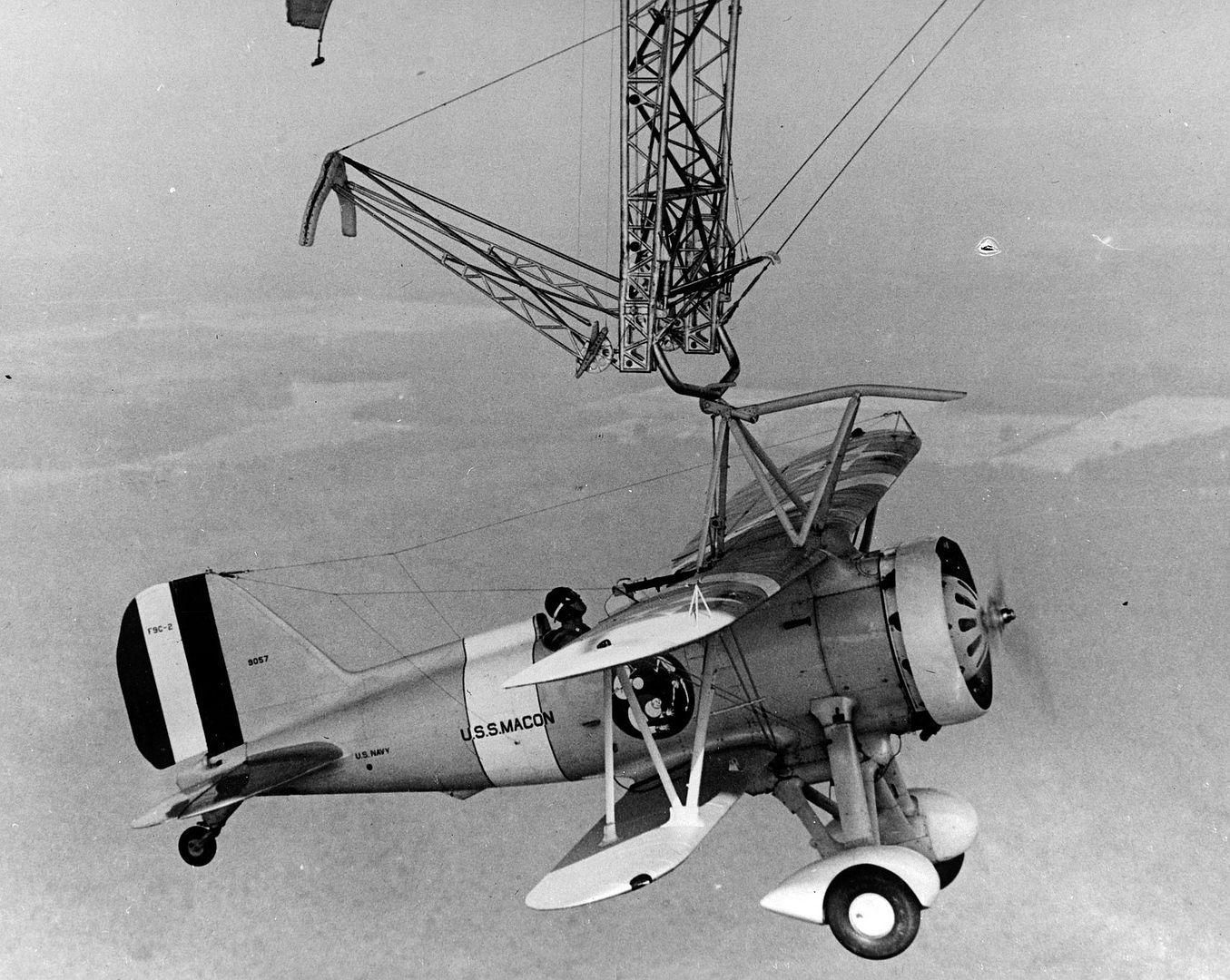

To achieve launching and recovery from the airship in flight, a 'skyhook' system was developed. The Sparrowhawk had a hook mounted above its top wing that attached to the cross-bar of a trapeze mounted on the carrier airship. For launching, the biplane's hook was engaged on the trapeze inside the airship's (internal) hangar, the trapeze was lowered clear of the hull into the (moving) airship's slipstream and, engine running, the Sparrowhawk would then disengage its hook and fall away from the airship. For recovery, the biplane would fly underneath its mother ship, until beneath the trapeze, climb up from below, and hook onto the cross-bar. The width of the trapeze cross-bar allowed a certain lateral lee-way in approach, the biplane's hook mounting had a guide rail to provide protection for the turning propeller (see photo), and engagement of the hook was automatic on positive contact between hook and trapeze. More than one attempt might have to be made before a successful engagement was achieved, for example in gusty conditions. Once the Sparrowhawk was securely caught, it could then be hoisted by the trapeze back within the airship's hull, the engine being cut as it passed the hangar door. Although seemingly a tricky maneuver, pilots soon learned the technique and it was described as being much easier than landing on a moving, pitching and rolling aircraft carrier. Almost inevitably, the pilots soon acquired the epithet "The men on the Flying Trapeze" and their aircraft were decorated with appropriate unit emblems.

Once the system was fully developed, in order to increase their scouting endurance while the airship was on over-water operations, the Sparrowhawks would have their landing gear removed and replaced by a fuel tank. When the airship was returning to base, the biplanes' landing gear would be replaced so that they could land independently again.

For much of their service with the airships, the Sparrowhawks' effectiveness was greatly hampered by their poor radio equipment, and they were effectively limited to remaining within sight of the airship. However, in 1934 new direction-finding sets and new voice radios were fitted which allowed operations beyond visual range, exploiting the extended range offered by the belly fuel tanks and allowing the more vulnerable mother ship to stay clear of trouble.

One interesting use of the Sparrowhawks was to act as 'flying ballast'. The airship could take off with additional ballast or fuel aboard instead of its airplanes. Once the airship was cruising, the aircraft would be flown aboard, the additional weight being supported by dynamic lift until the airship lightened.

Variants

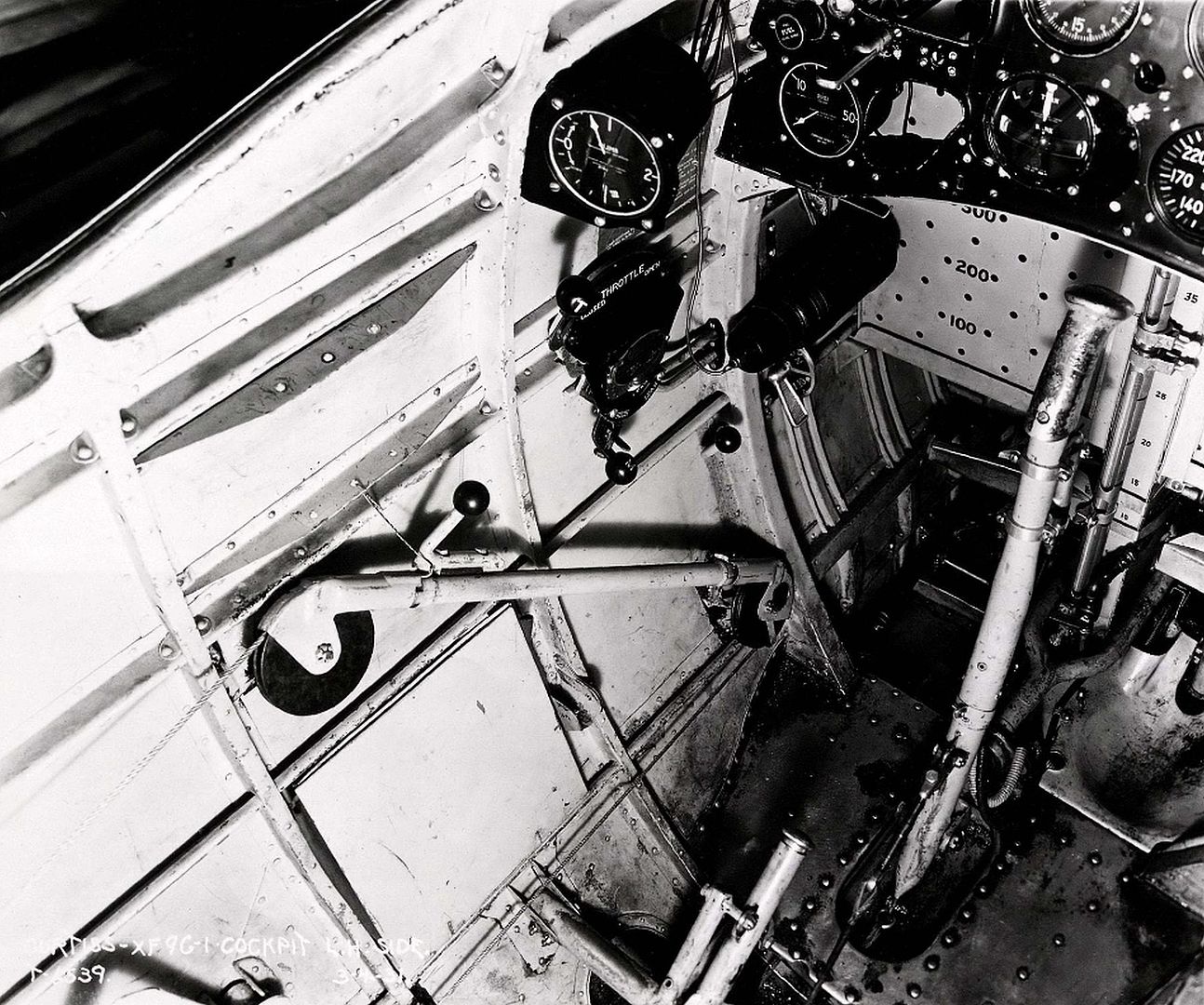

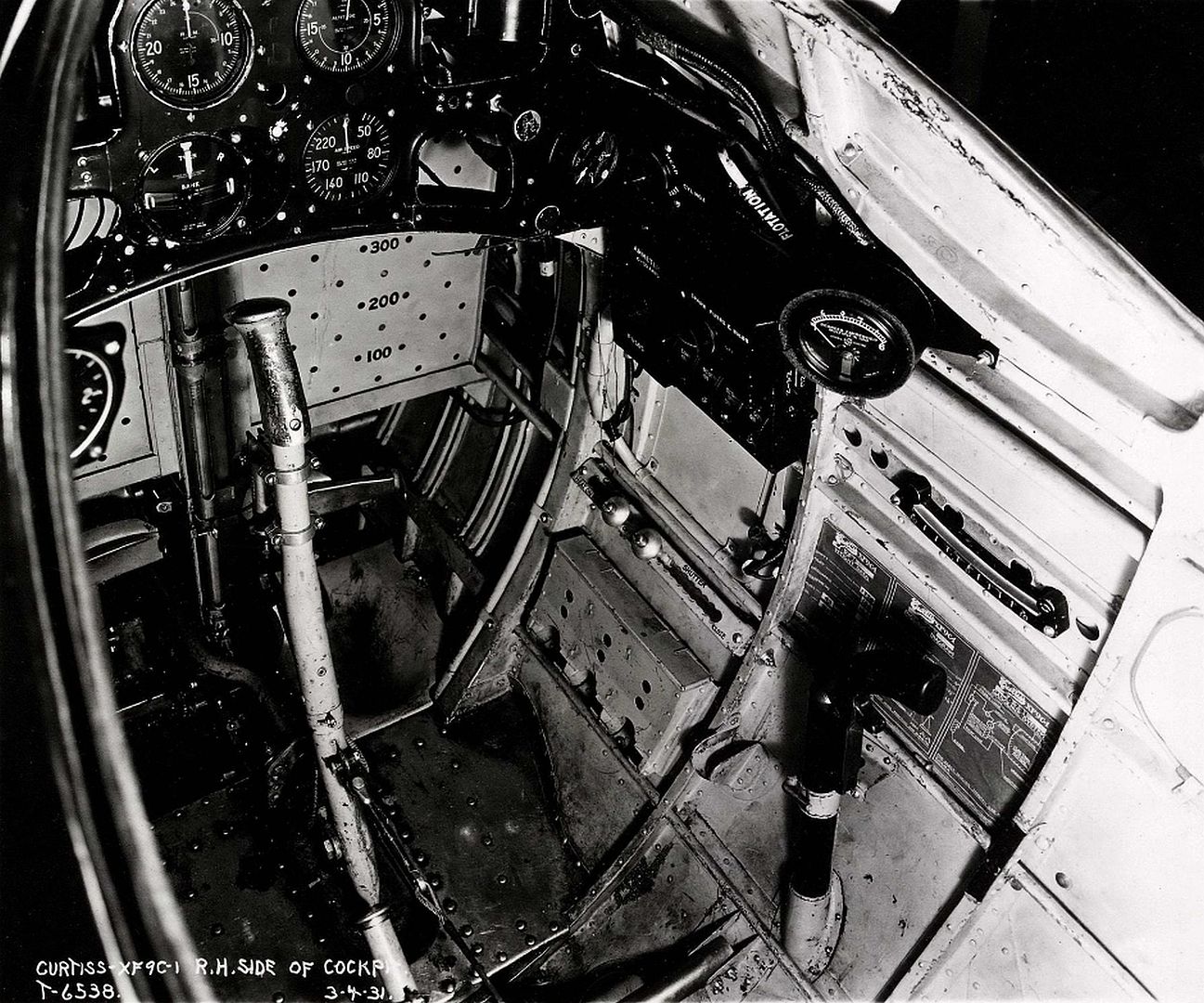

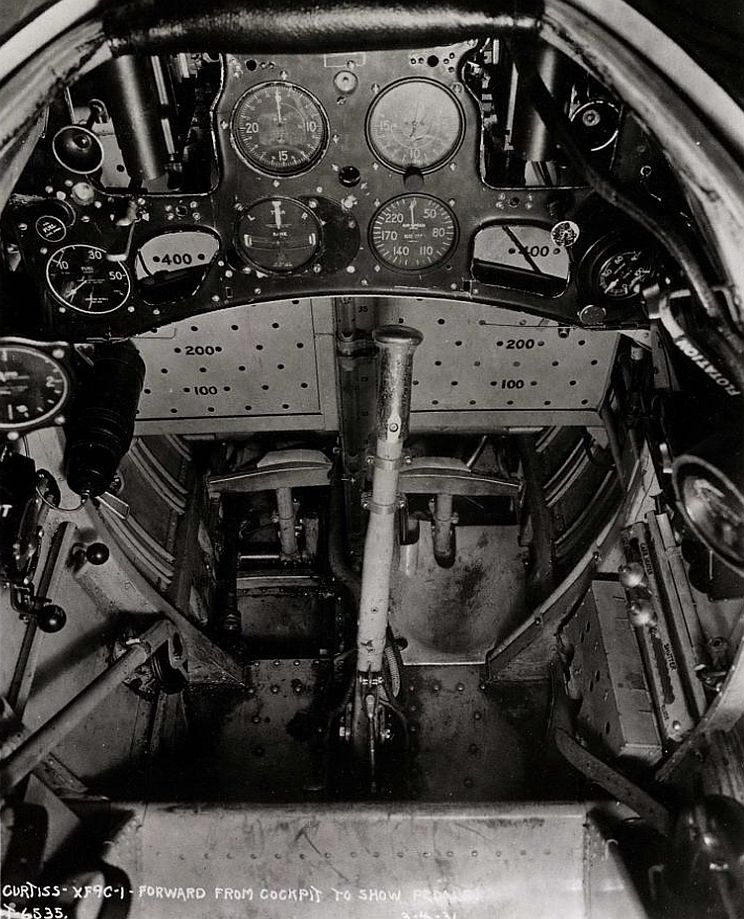

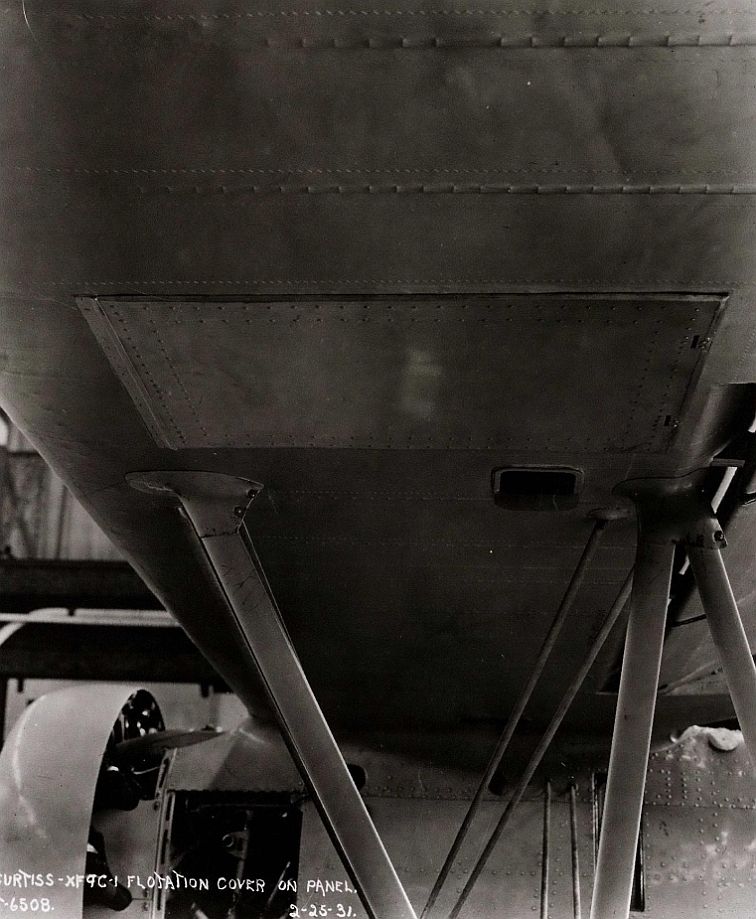

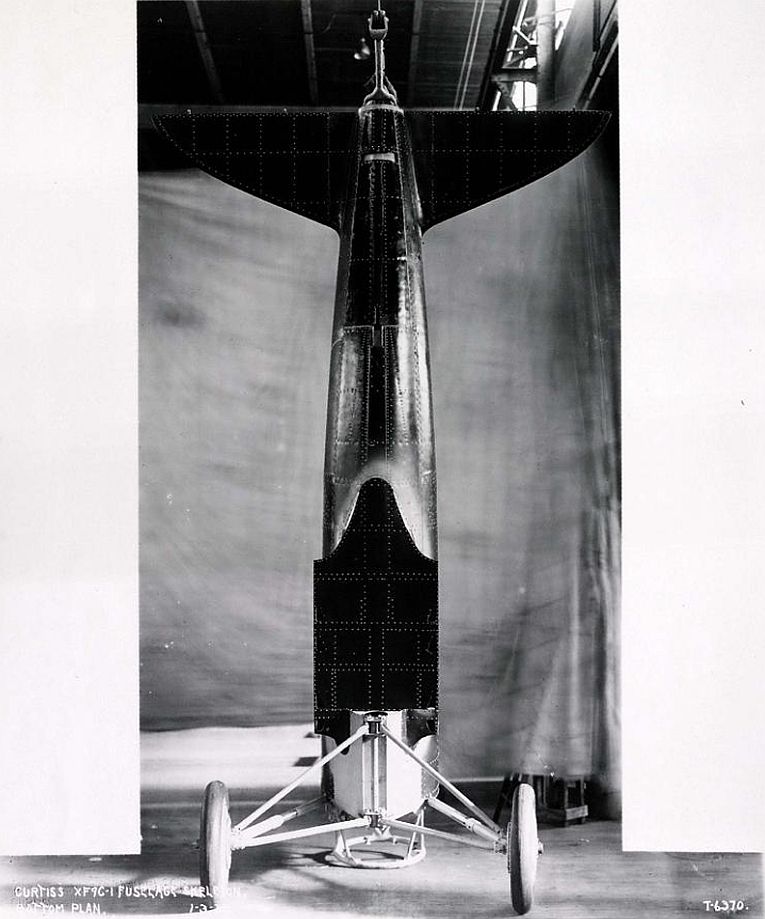

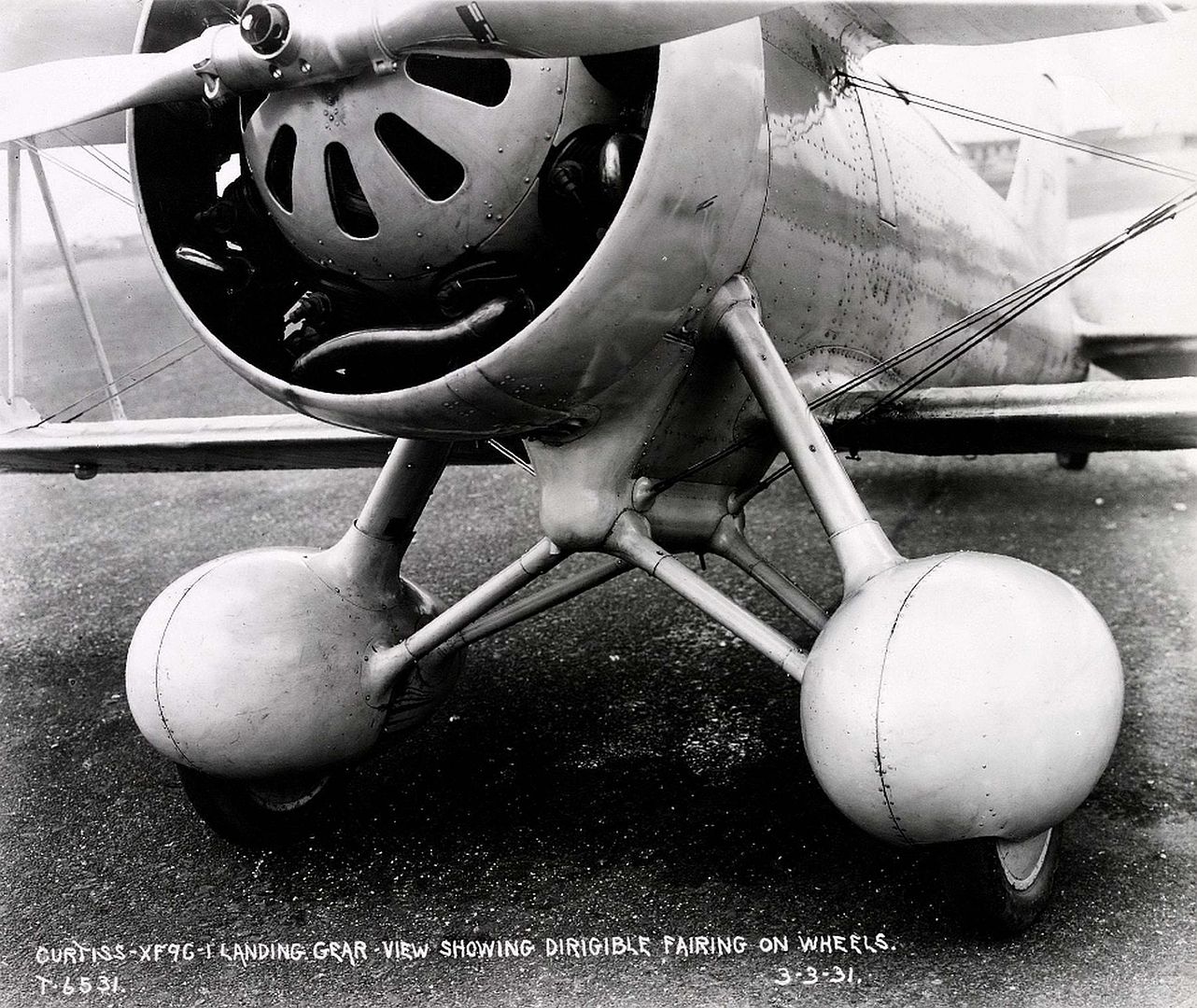

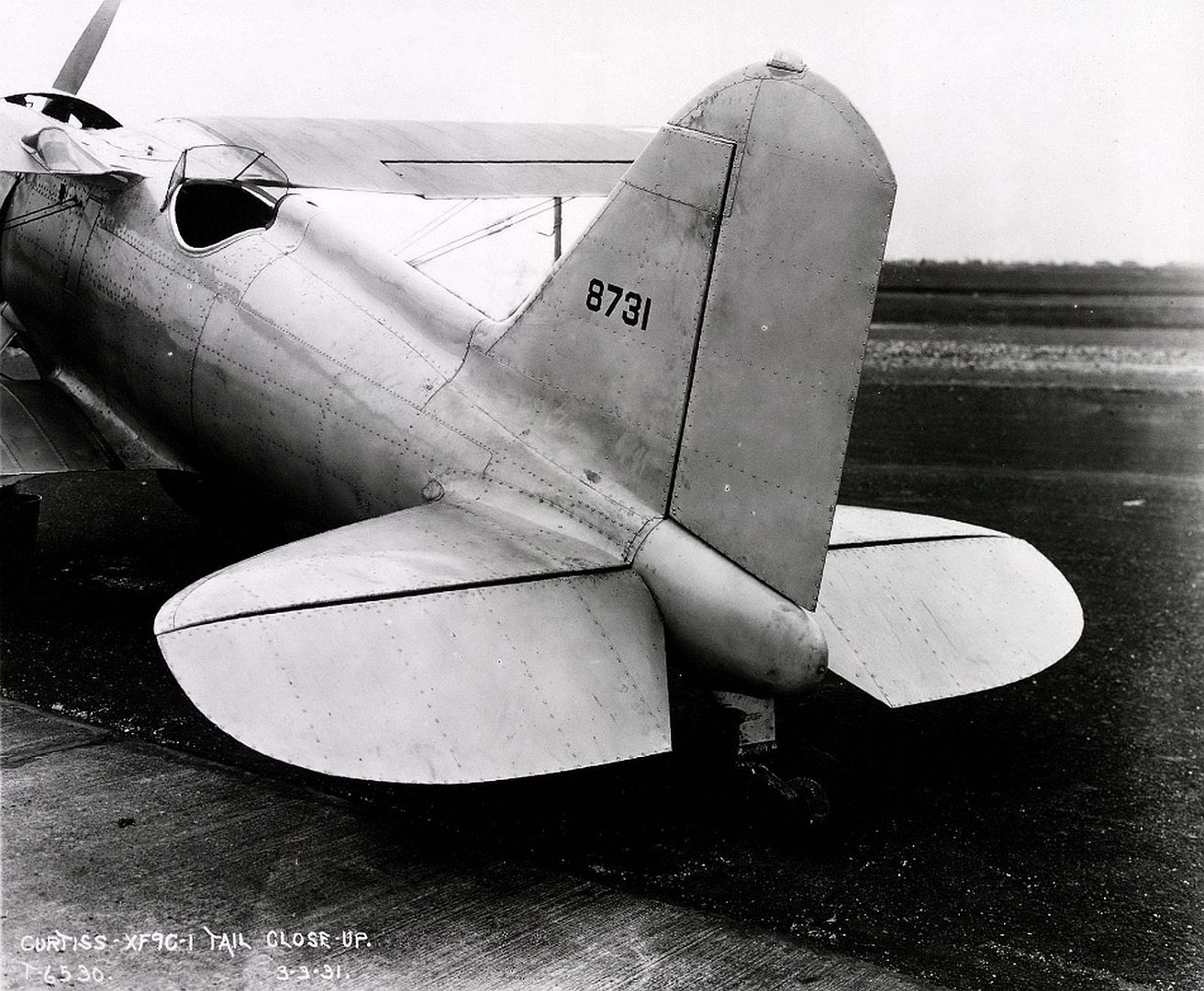

XF9C-1

First prototype. One built. BuAer number 8731. Scrapped in 1936.

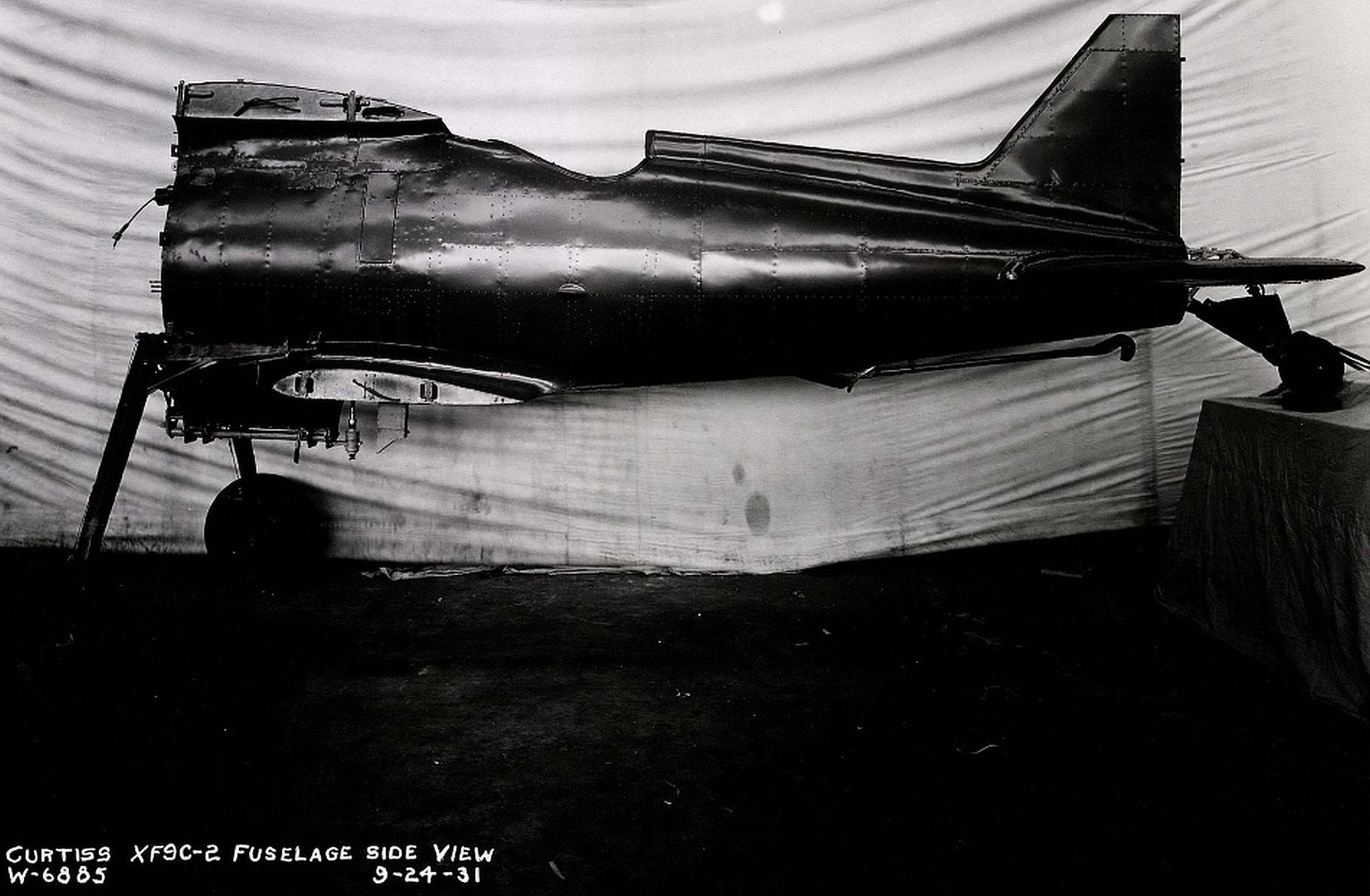

XF9C-2

Second prototype. One built. BuAer number 9264.

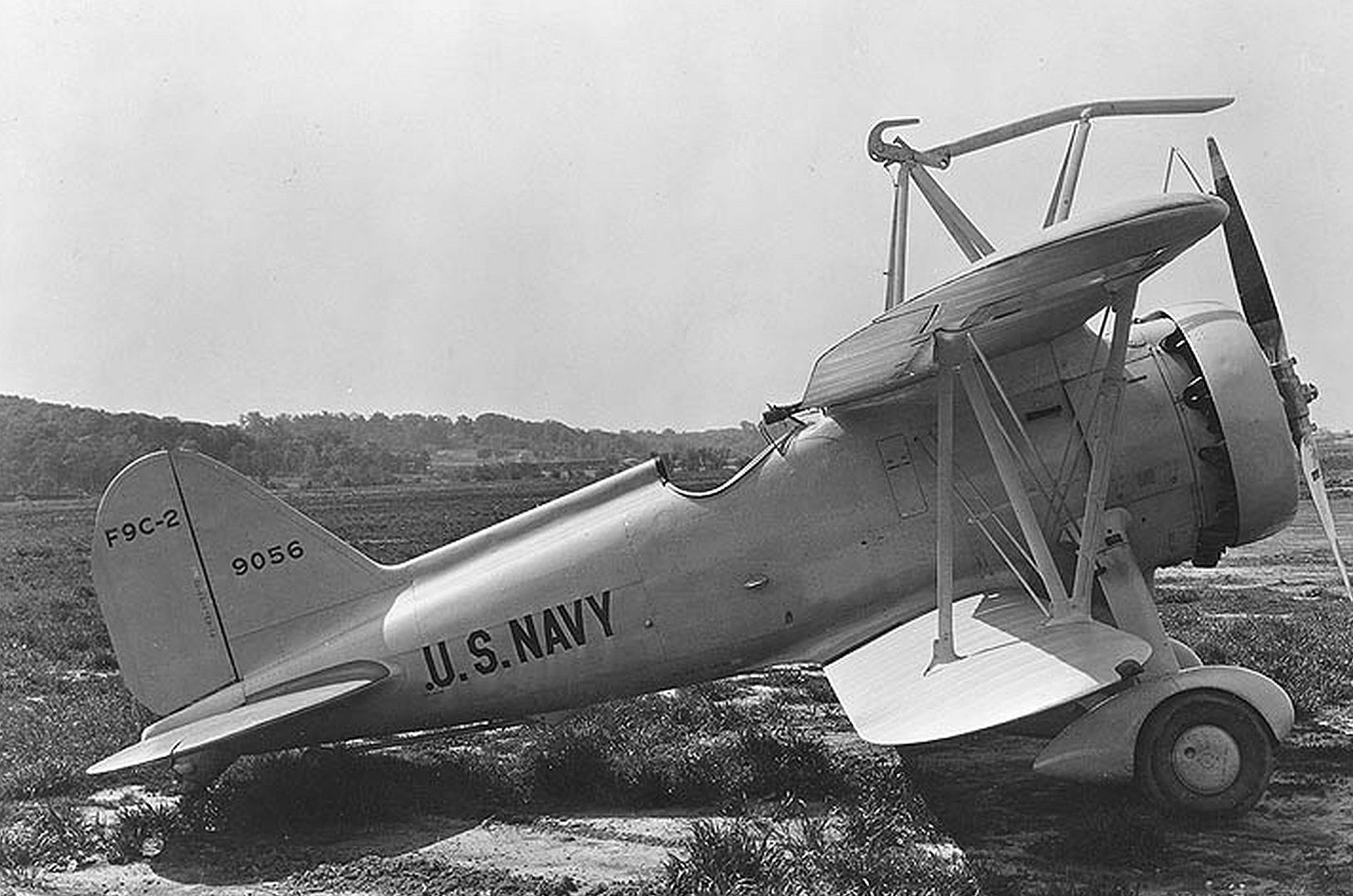

F9C-2 Sparrowhawk

Single-seat fighter biplane. 6 built. BuAer numbers 9056 - 9061

Specifications (F9C-2)

General characteristics

Crew: 1

Length: 20 ft 2.0 in (6.147 m)

Wingspan: 25 ft 6.0 in (7.772 m)

Height: 10 ft 6 in (3.2 m)

Wing area: 172.79 sq ft (16.053 m2)

Airfoil: Clark YH[12]

Empty weight: 2,089 lb (948 kg)

Gross weight: 2,776 lb (1,259 kg)

Powerplant: 1 × Wright R-975-E3 9-cyl. air-cooled radial piston engine, 438 hp (327 kW)

Performance

Maximum speed: 176.5 mph (284.0 km/h, 153.4 kn)

Range: 297 mi (478 km, 258 nmi)

Service ceiling: 19,200 ft (5,900 m)

Rate of climb: 1,700 ft/min (8.6 m/s)

Wing loading: 16 lb/sq ft (78 kg/m2)

Power/mass: 0.086 hp/lb (0.259 kW/kg)

Armament

Guns: 2 × .30 in (7.62 mm) Browning machine guns

Post a reply

- Go to Previous topic

- Go to Next topic

- Go to Welcome

- Go to Introduce Yourself

- Go to General Discussion

- Go to Screenshots, Images and Videos

- Go to Off topic

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinning Tips / Tutorials

- Go to Skin Requests

- Go to IJAAF Library

- Go to Luftwaffe Library

- Go to RAF Library

- Go to USAAF / USN Library

- Go to Misc Library

- Go to The Ops Room

- Go to Made in Germany

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Juri's Air-Raid Shelter

- Go to Campaigns and Missions

- Go to Works in Progress

- Go to Skinpacks

- Go to External Projects Discussion

- Go to Books & Resources